Opinion: People think chick flicks are bad but it’s simply not true

To mark International Women's Day, writer Amelia Yeomans examines the history of chick flicks, the value they hold - and why it's about time that we took the genre more seriously

Women not being taken seriously is hardly a new phenomenon. A tale as old as time, anything with femininity at its core is subject to needless ridicule and dismissal. One particular field that has suffered this fate is the world of cinema, resulting in arguably the greatest genre of all time: the chick flick.

A term that has come to encapsulate any narrative that centers on women, ‘chick flicks’ tend to be regarded pretty terribly in the cinema sphere. Originating in the late '80s, the phrase offered a simple way to separate women's interests from other media. Today, the genre is still very much alive and kicking - but does it have to be such a bad thing?

Off the back of her latest project, Hollywood superstar Reese Witherspoon recently stated "I don’t think I’ll ever stop making romantic comedies. It’s my favorite genre because it makes people feel good." Typically filed under the chick flick category, romantic movies aren’t usually sitting at the top of the Oscars nominations list. However, Witherspoon acknowledges the value of these movies in the simplest way - they make us feel good, without complication.

Anyone who remembers the heydays of the genre knows the value of a truly brilliant chick flick. Whether it’s experiencing Jenna Rink’s attempts to win back her childhood friendship in 13 Going On 30, or living through Cady and Regina’s rocky climb to the top of the social ladder in Mean Girls, there is no more comforting place to be.

But if you've ever found yourself in the position of suggesting a chick flick as evening entertainment, only to be met with eye rolls and grunts, you have witnessed the unfair reputation that chick flicks have been tainted with - but there is much more to the genre than the lighthearted movie posters suggest.

After the popularity of movies such as Steel Magnolias in 1989 and Thelma & Louise in 1991 and Sleepless in Seattle in 1993, it was clear that there was a real market for chick flicks. Widely considered the movie that began the 'chick flick' genre, Steel Magnolias followed the lives of a group of women facing struggles with health, marriage, motherhood and relationships. This exploration of the everyday aspects of womanhood, not sugar-coated or made aesthetically pleasing for the male eye, was exactly what audiences had been missing.

Women were finally able to see themselves represented in a way that they identified with. No longer a visual accessory, women had the chance to explore their own interests outside of a male-framed narrative. Chick flicks represented women finally having true agency - something long rejected by traditional cinema.

Sign up to our free daily email for the latest royal and entertainment news, interesting opinion, expert advice on styling and beauty trends, and no-nonsense guides to the health and wellness questions you want answered.

In her 1975 essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Laura Mulvey highlights the "silent image of woman still tied to her place as bearer of meaning, not the maker of meaning," on screen. This is also where Mulvey introduced the concept of the 'male gaze', which defined women as objects of visual pleasure for male viewers - being looked at as opposed to doing the looking. Going hand-in-hand, these two ideas demonstrate how women had been seen and used in cinema - until chick flicks became more common.

"Chick flicks represented women finally having true agency - something long rejected by traditional cinema."

Then came the time for women to tell their own stories with their own significance, occupying a new seat at the table. In 1989, the cult classic When Harry Met Sally made a staggering $92.8 million at the box office on its original release, while the even more popular Pretty Woman took home $178.41 million in 1990. Not only were women being portrayed on their own terms in these movies, but they were doing it with huge success.

But despite this cultural shift, the perception of women on and off-screen did not have a radical makeover - and the statistics inside the industry speak for themselves. A study by the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film, conducted in 2022, found that "women comprised 18% of directors, 19% of writers, 25% of executive producers, 31% of producers, 21% of editors, and 7% of cinematographers." With women still hugely underrepresented at every level, the push for their stories to be taken seriously becomes even more challenging.

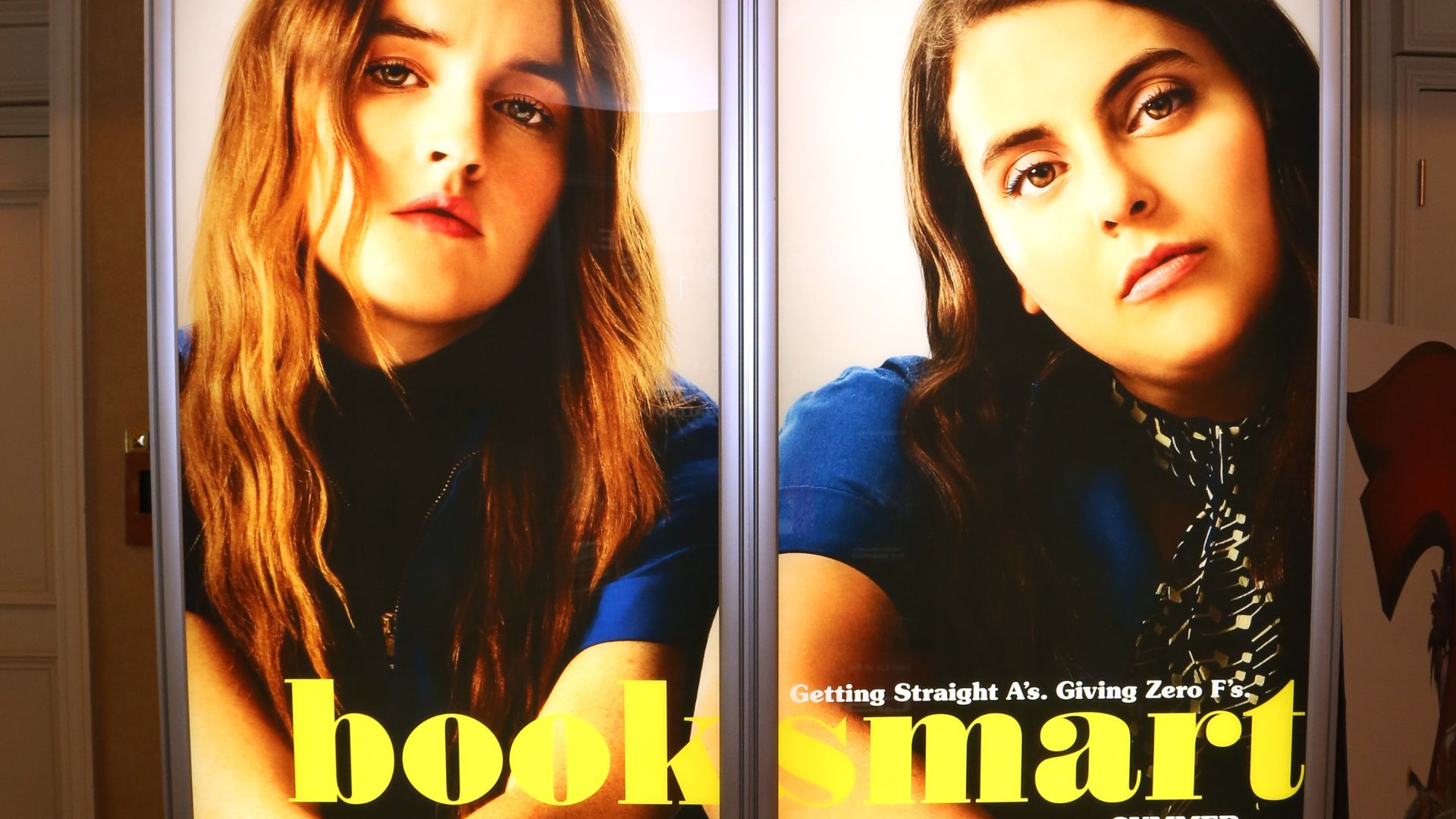

But that isn't to say it's impossible. Contemporary examples of movies such as 2019's Booksmart, which was written and directed by an all-female team, received huge praise from both critics and viewers. Angus, Thongs and Perfect Snogging directed by Gurinder Chadha in 2008 has come to define a generation of women who grew up in the early 2000s, and few chick flicks are quite as memorable. 2011's Bridesmaids, written by Annie Mumolo and Kristen Wiig, is undoubtedly one of history's most revered chick flicks. More recently, Gen Z hits like 2018's To All the Boys I've Loved Before not only represent progress in terms of on-screen diversity but also demonstrate that the desire for female-written narratives is stronger than ever.

The reason for this lies in an obvious truth that chick flick fans have known for decades - they are undeniably entertaining. Movies with near enough identical plots featuring male protagonists are categorized appropriately: comedy, drama, thriller, and epic. They are also appreciated and celebrated appropriately.

Yet replace this main character with a woman and the filing system will almost automatically determine it to be a chick flick. Miss Congeniality, a 2011 movie about an undercover FBI agent working to take down a domestic terrorist, should surely slot into the action category. But owing to the female protagonist, and setting in a beauty pageant, chick flick becomes the default.

A further issue lies in the fact that movies belonging to this genre are typically seen as shallow. Just look at Legally Blonde, which despite telling the story of a woman achieving a law degree from one of the best schools in the world, is defined by its feminine characters and self-aware humor that is then used to dismiss it. Easy A, released nine years later in 2010, taught me a significant amount about teenage relationships and self-worth, yet I have never seen anyone besides women discuss its value.

However, the chick flick label doesn’t have to be fundamentally bad. In fact, I am extremely grateful for it. I can be certain that anything attached to it will bring me solace and joy - it acts as my happiness cheat sheet that feels more intimate and sacred because not everyone understands its worth. How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days and The Devil Wears Prada were among the movies that made me want to pursue a career in magazines and writing, while the Sex and the City movie told me so much about the value of female friendships.

Yes, some chick flicks are silly, light-hearted, and intended to be taken with a pinch of salt, but that doesn't mean that they should be regarded any differently to chick flicks with more serious undertones. The Hangover or Zoolander are seen as worthwhile solely because they are trivial and entertaining, and it's about time that movies made by, centered around and enjoyed by women are given the same courtesy.

Whether you love chick flicks for what they represent about womanhood and liberation, or just enjoy being transported to the dream-like, stylized world of the big screen, they hold a tremendous amount of value that cannot be overlooked. Celebrate the label in all its glory and have no shame about it.

Amelia joined woman&home in 2022 after graduating with an MA in Magazine Journalism from City University and she is now a senior fashion and beauty writer. She began building her career as a lifestyle journalist after completing a fashion journalism course at the Condé Nast College of Fashion & Design in 2019, writing for a variety of titles including OK!, New!, and Notion on topics such as sustainable fashion and entertainment.