Power, purpose, and a bold second act: Meet the women who changed the world later in life

Think it's too late to make history? Think again...

Sign up to our free daily email for the latest royal and entertainment news, interesting opinion, expert advice on styling and beauty trends, and no-nonsense guides to the health and wellness questions you want answered.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

woman&home Daily

Get all the latest beauty, fashion, home, health and wellbeing advice and trends, plus all the latest celebrity news and more.

Monthly

woman&home Royal Report

Get all the latest news from the Palace, including in-depth analysis, the best in royal fashion, and upcoming events from our royal experts.

Monthly

woman&home Book Club

Foster your love of reading with our all-new online book club, filled with editor picks, author insights and much more.

Monthly

woman&home Cosmic Report

Astrologer Kirsty Gallagher explores key astrological transits and themes, meditations, practices and crystals to help navigate the weeks ahead.

There are many ways to define a powerful woman. She might be a bestselling author, a record-breaking athlete, or a celebrity who millions adore… but this isn’t that list. This list celebrates something different: women who didn’t just leave a mark on history, they altered its course. And not only that, they did it later in life, at a time when society is often quick to write women off!

Yes, we honour heroines like Boudica, Joan of Arc, Sacagawea and Rani Lakshmibai, but this isn’t their list either. This is about women who took the world as it was and, in their 40s, 50s, 60s and beyond, changed it forever. Without their voice, vision, or leadership, history would look radically different.

From royals to rebels, humanitarians to hardliners, these are the women who proved that it’s never too late to make history.

Women who changed the world later in life

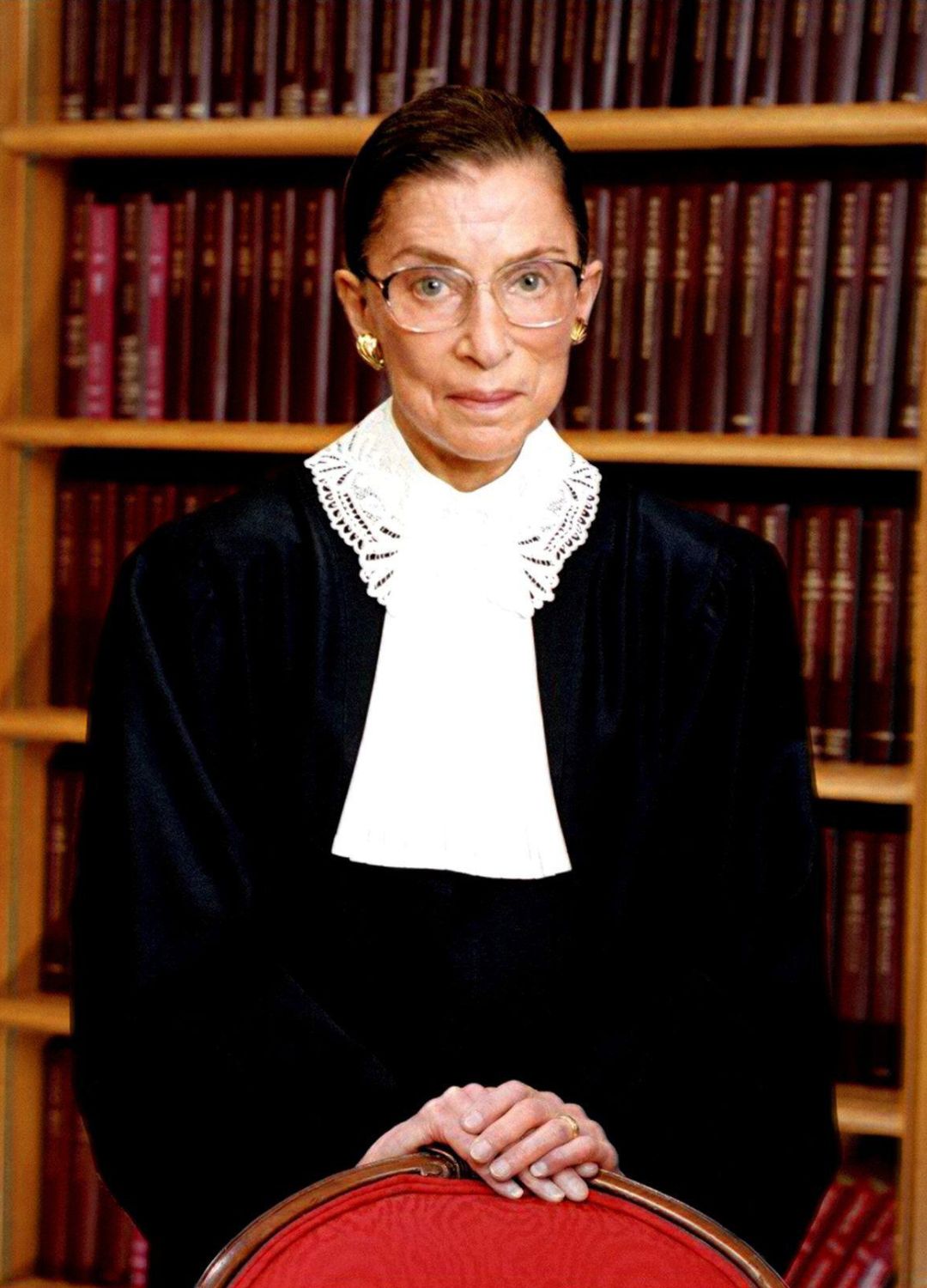

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Nicknamed “The Notorious R.B.G.” and a beloved pop culture icon in her 80s, Ruth Bader Ginsburg showed us that influence has no age limit. A brilliant lawyer and professor, she spent decades fighting for gender equality.

Ruth co-founded the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project in the 1970s, where she argued and won five out of six landmark cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, each one chipping away at laws that discriminated on the basis of sex.

But it wasn’t until she was appointed to the Supreme Court at the age of 60 that she really hit her stride. From then on, she became a powerful voice on everything from equal pay and abortion rights to health care and civil liberties. Her sharp dissents made waves, her lace collars made headlines, and her quiet determination made her a hero across generations.

Rosa Parks

Though already active in the fight for civil rights, Rosa Parks became a global icon at 42 after sparking the Montgomery Bus Boycott. By refusing to give up her seat to a white man, Rosa's act of defiance became a hugely pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement.

Sign up to our free daily email for the latest royal and entertainment news, interesting opinion, expert advice on styling and beauty trends, and no-nonsense guides to the health and wellness questions you want answered.

Over the next four decades, Rosa continued her activism in Detroit, fighting housing discrimination, police brutality, and supporting Black communities through both grassroots action and political work, including her role with Congressman John Conyers.

She also marched on Washington for jobs and freedom, and co-founded a youth leadership institute to empower the next generation of Black activists. At 81, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, proving it’s never too late to fight for what’s right.

Mother Teresa

Feeling called to religious life at just 12, Agnes Gonxha Bojaxhiu joined the church and became a teacher in Calcutta. But everything changed at 36 when she felt a second divine calling: to live among and care for the poorest of the poor.

Now known as Mother Teresa, she founded the Missionaries of Charity in her 40s and spent the rest of her life, along with her helpers, building homes for orphans, hospices for the dying, and leprosy centres in over 100 countries.

She devoted herself to the sick, dying, and destitute wherever she was needed, helping the hungry in Ethiopia, radiation victims at Chernobyl, and earthquake survivors in Armenia, and at 69, she received the Nobel Peace Prize. Never to be forgotten, in 2016, 19 years after her death, she was canonised by Pope Francis as Saint Teresa of Calcutta.

Hypatia

Revered as the original woman of science, Hypatia of Alexandria was brilliant, bold, and centuries ahead of her time. In an era when women were expected to stay silent in the shadows, it was almost unthinkable that, in the mid-to-late 300s CE, Hypatia would rise to lead the Neoplatonist school in Alexandria, teaching advanced mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy, drawn from thinkers like Plato and Aristotle, to students from across the Mediterranean.

By the 400s, in her late 40s, she was writing respected commentaries on Arithmetica and Conics, and refining scientific tools like the astrolabe (used to track stars and planets) and the hydrometer (used to measure the density of liquids). Hypatia was tragically murdered by a mob in 415 CE, during a time of rising political and religious unrest in Alexandria. But her death marked more than the loss of a brilliant mind, it symbolised the end of an era of classical learning.

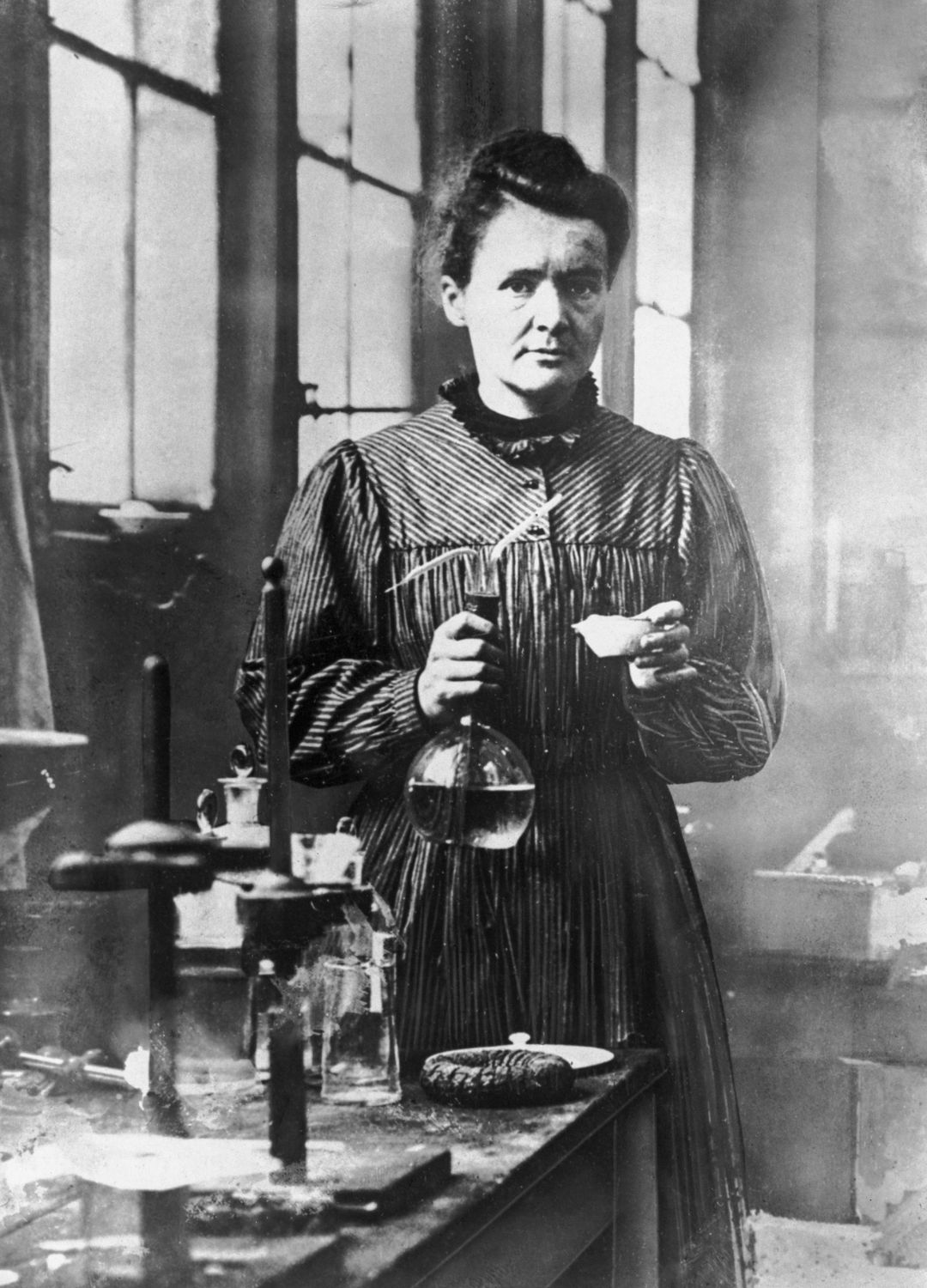

Marie Curie

Together with her husband and research partner Pierre Curie, Marie discovered the elements polonium and radium, a feat that earned them the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics. But it was years after Pierre’s tragic death, when Marie was in her 40s, that she truly cemented her own pioneering role.

At 44, she won a second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry, becoming the first person ever to receive Nobels in two scientific fields. She later developed mobile X-ray units to treat wounded soldiers during World War I and laid the foundation for modern cancer therapies and nuclear science.

Queen Elizabeth I

Highly intelligent and majestically strong-willed, Queen Elizabeth I was the brilliant, formidable heir whom Henry VIII split a kingdom for, yet he never imagined she would outshine every king who came before her, let alone assert herself as one of the most powerful monarchs in European history.

Although she ascended the throne at 25, it wasn’t until her 40s that she truly found her stride. Holding firm to her independence as the 'Virgin Queen', she devoted herself entirely to her country, ushering in a period of rare stability, where she skilfully navigated religious tensions and neutralised foreign threats.

Under her leadership, the Elizabethan era blossomed into a true “Golden Age”, a time of cultural renaissance that saw the rise of literary greats like Shakespeare and Marlowe, and bold exploration of the New World by adventurers like Sir Walter Raleigh. National pride soared when her navy defeated the Spanish Armada in her mid-fifties, securing England’s status as a global force. She ruled until her death in 1603, aged 69, leaving behind a legacy of power, poise, and unparalleled presence.

Stephanie Kwolek

Stephanie Kwolek wasn’t interested in becoming famous; she just loved chemistry. Born in the U.S. to Polish immigrant parents, she changed the world at 46 when she invented Kevlar, a fibre five times stronger than steel, now used in bulletproof vests, helmets, and aircraft, ensuring her name would always be remembered.

But far from a one-hit wonder, Stephanie earned 28 patents during her career and contributed to materials like Spandex and Nomex. After retiring, she devoted herself to mentoring young scientists, especially girls, and at 72, was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame and became the first woman to receive DuPont’s Lavoisier Medal.

The following year, she was awarded the U.S. National Medal of Technology and Innovation, as well as the Perkin Medal, and at 80, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Her final honour came in 2014, when the Royal Society of Chemistry named an award after her, just after she passed away, aged 90.

Ruth Handler

We all know Barbie; the blonde bombshell who’s been everything from astronaut to architect, but did you know the woman who invented her, Mattel co-founder and president Ruth Handler, did something arguably even more powerful after her doll days? In her 50s, Ruth survived breast cancer and a mastectomy, only to find the prosthetics available were uncomfortable and unconvincing. So what did she do? She invented her own!

“Nearly Me” was one of the first realistic breast prosthetics, giving post-surgery women comfort and confidence. Not only that, but it helped to earn her the title Woman of the Year in Business from the Los Angeles Times. And that wasn’t the only recognition she would receive for her contribution to the world, as in 1989, she was inducted into the Toy Industry Hall of Fame, and later received the American Cancer Society’s Volunteer Achievement Award.

She was also the inaugural Woman of Distinction recognised by the United Jewish Appeal, perfectly fitting tributes to a woman who helped millions feel seen, strong, and unstoppable.

Beulah Louise Henry

Often referred to as the “Lady Edison,” Beulah Louise Henry was a prolific American inventor who secured 49 U.S. patents and is credited with over 100 inventions. Many of her most impactful creations emerged after turning 40, with notable innovations including a bobbin-free sewing machine, snap-on umbrella covers, the Protograph (a typewriter accessory that produced multiple copies without carbon paper), continuously-attached envelopes for mass mailings, and various toys and household devices.

Remarkably, Henry achieved all this without formal engineering training, instead collaborating with model makers to bring her ideas to fruition. Her inventive career remained active well into her 60s, leaving a lasting impact on both domestic life and industrial manufacturing.

Grace Hopper

Nicknamed “Amazing Grace,” Grace Hopper was a pioneer of computer programming at a time when the industry was dominated by men. In 1949, aged 43, she invented the first compiler (making coding more accessible) and co-developed COBOL, a business language still in use today.

While she worked on early computing machines like the Harvard Mark I and UNIVAC I & II, her true legacy lies in revolutionising how we write software, and she was a champion of tech education right up until her death at 85. Not content with just shattering tech’s glass ceiling, at 79 she became a Rear Admiral, making her the oldest active-duty commissioned officer in the U.S. Navy at the time, an incredibly rare feat for a woman.

Katherine Johnson

Katherine Johnson, a brilliant mathematician, broke barriers throughout her life. In her 30s, she joined NACA (the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, a precursor to NASA) as part of the West Area Computing unit, where Black women manually performed critical spaceflight calculations under segregated conditions.

At 43, she calculated the trajectory for America’s first human spaceflight, and a year later, verified astronaut John Glenn’s orbital path, at his specific request. At 50, she contributed to the successful Apollo 11 moon landing, and at 51, supported calculations that led to the safe return of Apollo 13.

Her legacy as a Black woman in STEM continues to inspire generations, and in 2016, NASA named the Katherine G. Johnson Computational Research Facility in her honour. That same year, her extraordinary story reached a global audience through Hidden Figures, the bestselling book and Hollywood film that revealed the racism and sexism she overcame to help shape space history.

At 97, she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and, four years after her death at 101, was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2024.

Eleanor Roosevelt

Eleanor Roosevelt didn’t just stand behind a great man; she stepped out in front and changed the world herself. Born in 1884, she became America’s longest-serving First Lady and redefined the role in her 50s, travelling the country to report on poverty and influence New Deal policies (laws that would seek to alleviate the devastation caused by the Great Depression).

A tireless advocate for civil rights, she backed anti-lynching laws, resigned from the Daughters of the American Revolution over racial injustice, and held over 300 press conferences exclusively for female journalists.

In her 60s, she became the first U.S. delegate to the UN Human Rights Commission, helping draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. While in her 70s, she chaired JFK’s Commission on the Status of Women. Unquestionably, as one of the 20th century’s most influential people, Eleanor left a legacy of fearless advocacy for the voiceless.

Florence Nightingale

With her laser-like focus on hygiene, fresh air, and sanitation, which drastically reduced death rates, not to mention her pioneering coxcomb charts (a modified pie chart) that used data to expose preventable deaths, Florence Nightingale rose to fame in her late thirties during the Crimean War (1853-56).

Although she went on to suffer from brucellosis, contracted during the war, she founded the Nightingale Training School for Nurses, educating generations of women in evidence-based care and raising the standards of nursing worldwide. In her 40s and 50s, she led sweeping hospital reform in Britain, improving ventilation, cleanliness, and patient care, while in her 50s and 60s, she advised on public health in India, promoting sanitation and disease prevention.

Recognised for her lifelong pursuit of better healthcare, which saved, and continues to save, countless lives, she was awarded the Royal Red Cross at 63 (1883), appointed a Lady of Grace of the Order of St John at 84 (1904), and became the first woman to receive the Order of Merit at 87 (1907).

Catherine the Great

Move over, Alexander and Peter, because Catherine may have been the greatest Great of them all. Born Sophie Friederike Auguste in a German principality (now part of Poland) in 1729, Catherine II of Russia didn’t just marry into royalty; she seized the throne from her unpopular husband, Tsar Peter III, just six months after he became emperor, when she was 33.

With his abdication and the backing of the army and key nobles, Catherine wasted no time. She expanded Russia’s borders, reformed education with state schools and Europe’s first state-funded higher education institution for women, and transformed the Hermitage into a world-class museum. She corresponded with Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire and Diderot, all while navigating palace politics and a famously colourful love life with flair. Catherine ruled for 34 years, making her the longest-reigning female monarch of Russia, and proving that you don’t need to have royal blood to be a Queen.

Madam C. J. Walker

Creating her own line of haircare products for Black women when few existed, Madam C.J. Walker became America’s first self-made female millionaire. After starting as a sales agent for Annie Turnbo Malone, she launched her own business in her late 30s with “Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower,” a scalp formula inspired by her own hair loss, while later products include: Glossine, Vegetable Shampoo, and Tetter Salve.

Madam C.J. Walker oversaw production and branding in her own factory and trained thousands of Black women to sell her products, which at the time was a revolutionary model of empowerment. By opening salons and schools across the U.S, she helped women gain financial independence in the face of racial and gender inequality.

Not one to squander her wealth, she became a major philanthropist and, in her 50s, donated to schools, funded scholarships, and financially supported the NAACP’s anti-lynching fund, while her estate, Villa Lewaro, became a hub for Black leaders. Her legacy endures as a trailblazer of beauty, business, and Black women’s liberation.

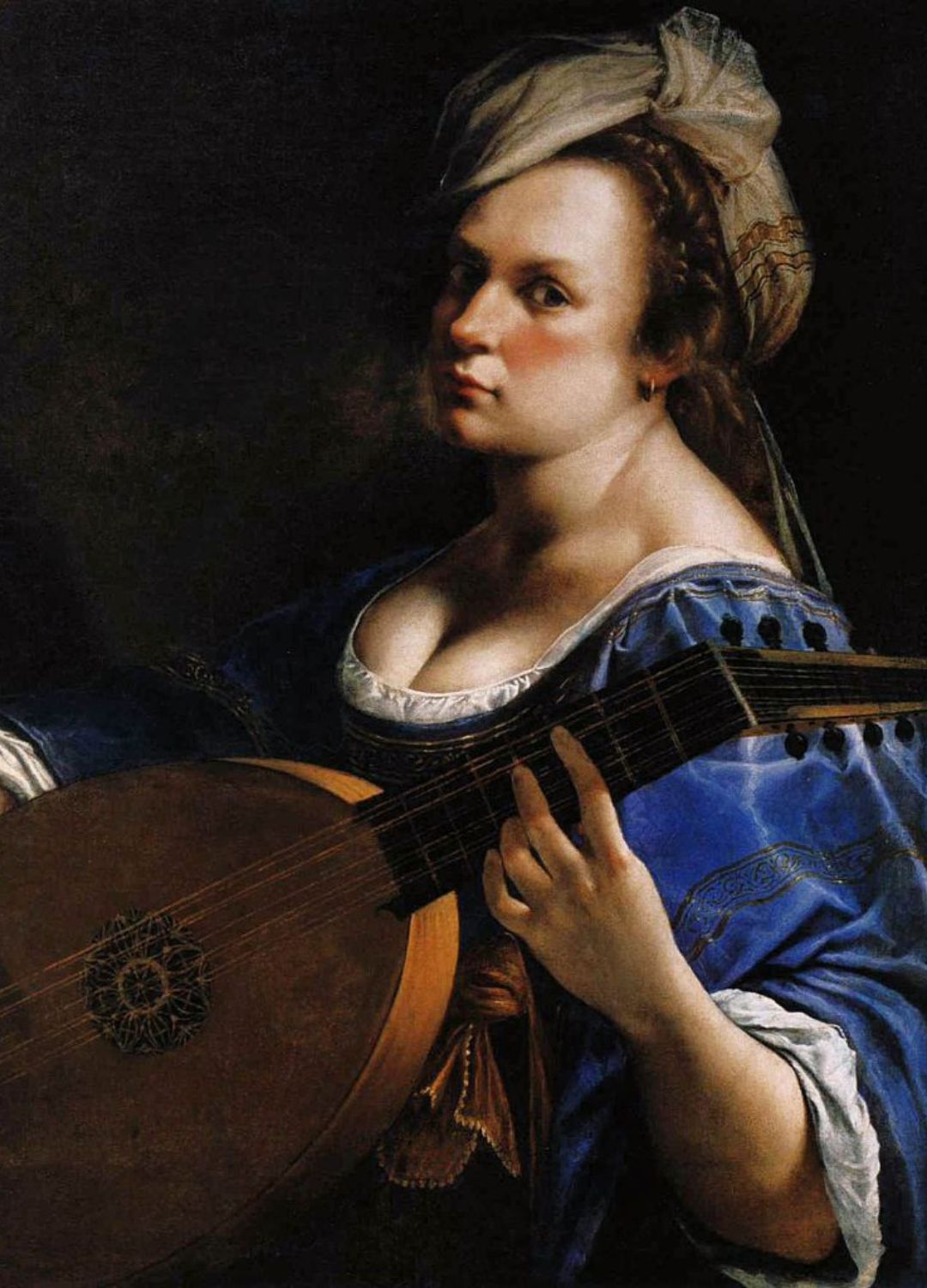

Artemisia Gentileschi

Artemisia Gentileschi may not have been the world's first female painter, but she was one of the first to gain international fame, and she was every bit as successful as her male peers.

After surviving a traumatic assault by her tutor and a gruelling public trial in her teens, she refused to be silenced, and her bravery has echoed through history, with themes of justice, female strength, and survival woven through her work. She went on to become the first woman admitted to Florence’s Accademia delle Arti del Disegno, but it was in her 40s and 50s that she truly hit her stride.

Settling in Naples around 1630, Artemisia ran a thriving workshop and took on high-profile commissions across Europe. Her later masterpieces, like Judith and Her Maidservant and Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, the latter completed under the patronage of King Charles I in London, captured powerful, complex women in all their fury, grace, and resilience. These weren’t just paintings; they were bold, defiant statements that continue to speak volumes, 400 years later.

Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst was already a prominent suffragist when, at 45, she founded the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. She had previously established the Women's Franchise League in 1889, which fought for married women's right to vote in local elections, yet frustrated by the slow pace of peaceful advocacy, she led the WSPU in a militant campaign.

During this time, she organised protests, hunger strikes, and acts of civil disobedience. Her daughters, Christabel and Sylvia, were also heavily involved, alongside hundreds of fellow suffragettes. This period of militancy ended with the outbreak of World War I in 1914, when Emmeline redirected her efforts to support the war.

Her unwavering dedication helped lead to the Representation of the People Act 1918, which granted voting rights to women over 30, and although she died on 14 June 1928, just before women won equal voting rights with men, that milestone would not have been achieved without her.

Empress Theodora

Theodora’s story reads like the plot of a gripping historical drama. Born around 497 CE to a bear-keeper and raised in the bustling heart of Constantinople, she began life as an actress, which was considered a scandalous profession at the time.

But her sharp mind, unshakable resolve, and natural charisma caught the attention of Justinian I, heir to the Byzantine throne, and in a true rags-to-riches romance, they fell in love and married, though a special law had to be passed to allow it.

But it wasn’t until her late forties and fifties that Theodora truly came into her own. As empress, she pushed through reforms to improve the lives of women, outlawing human trafficking, improving divorce laws, and establishing safe spaces for those in need.

She also defended persecuted religious minorities, quietly but powerfully shaping policy from behind the scenes. When violent riots threatened to tear the empire apart, it was Theodora who famously refused to flee. Her bold declaration, “Royal purple makes a fine burial shroud”, is said to have changed the course of history and saved Justinian’s reign.

After her death in 548 CE, thought to be from cancer, the pace of new legislation noticeably slowed, proof, if any were needed, of the vital role she played at the heart of Byzantine power.

Laura Bassi

Said to be the world’s first female professor, Laura Bassi didn’t just open the door for women in science, she held it wide open for others to follow. Born in Bologna in 1711, Laura was a child prodigy who made headlines in her twenties as the first woman in Europe to earn a doctorate in science.

Soon after, she was appointed professor of natural philosophy (physics), which was an extraordinary achievement for any woman in the 18th century. Though initially barred from teaching publicly, Laura turned her home into a buzzing science hub, where she conducted experiments, mentored young scholars, and brought complex Newtonian ideas to life, making science accessible and playing a key role in spreading Enlightenment thinking beyond academic circles.

Throughout her 40s and 50s, Laura published widely, earned respect across Europe, and became a member of Italy’s prestigious Academy of Sciences, all while raising eight children!

Then, at 65, she smashed yet another ceiling when she became the first woman with a paid position in experimental physics at Bologna’s Institute of Sciences, finally gaining full access to labs and resources. Laura’s work helped pave the way for women in academia and science, not just in her era but for centuries to come.

Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil

She might not have worn the crown, but Princess Isabel of Brazil came closer than any other woman in the nation’s history. As the daughter and heir of Emperor Pedro II, she was Brazil’s Princess Imperial, an empress-in-waiting.

While she never officially ruled as monarch, she stepped up as regent three times, but it was during her third and final turn, at the age of 41, that she made history. In 1888, while governing in her father’s absence, Isabel signed the Golden Law, abolishing slavery in Brazil, making it the last country in the Western world to do so.

It was a courageous, compassionate act that earned her the nickname “The Redemptress” and praise from Pope Leo XIII, who awarded her the Golden Rose, a rare papal honour. But the decision also angered and alienated Brazil’s powerful landowning elite, directly contributing to the fall of the monarchy just one year later, in 1889.

Isabel spent the rest of her life in exile in France, where she supported religious charities, raised her family, and led a quiet life. Though she never returned to the political arena, she is remembered as a woman who used her power not for glory, but for justice.

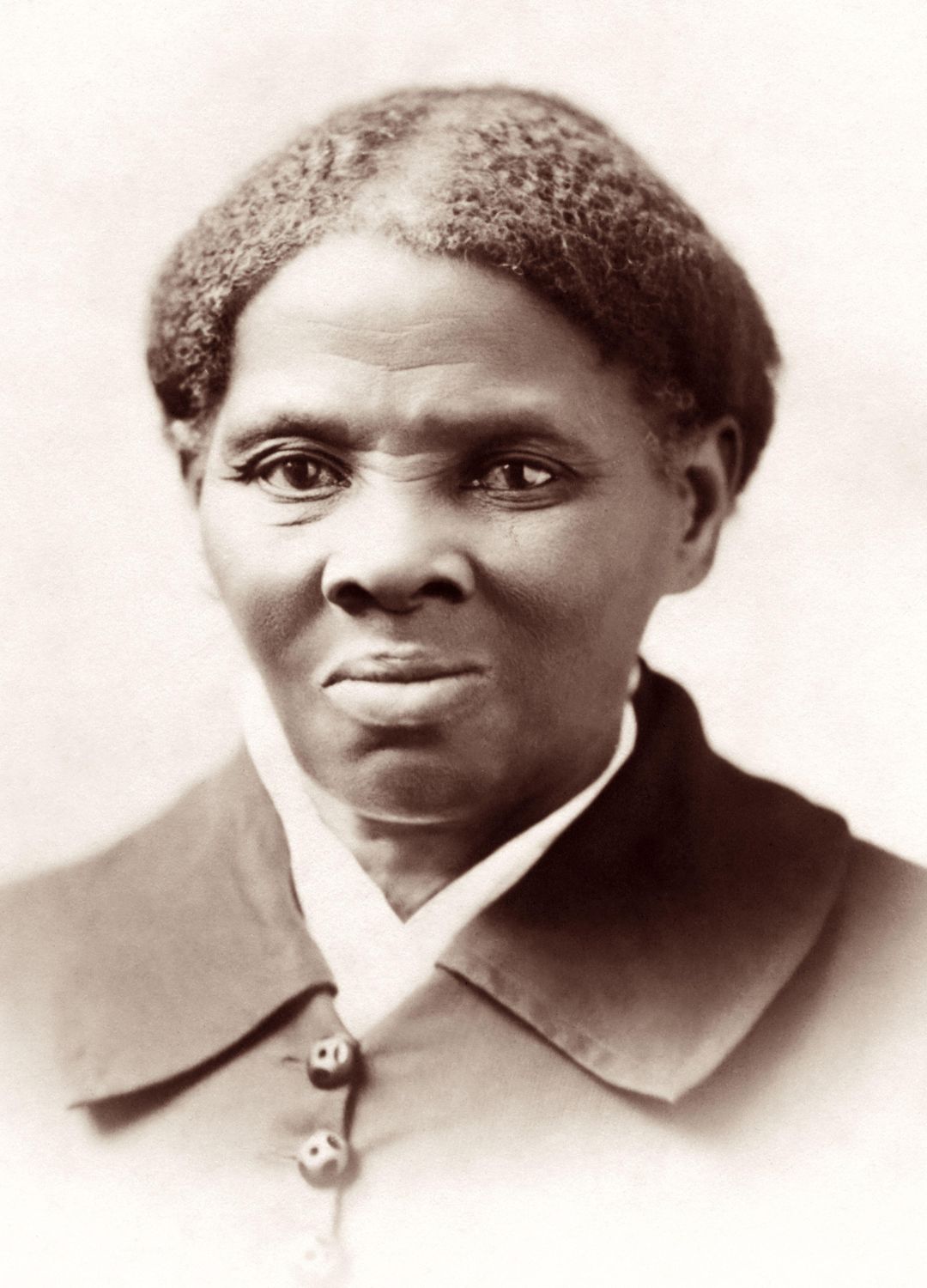

Harriet Tubman

Born into slavery in 1822 but escaping in 1849, Harriet Tubman was a brave and determined woman who led approximately 70 enslaved people to safety through the Underground Railroad (a secret network of routes and safe houses), earning her the nickname “Moses”.

But her story didn’t end there. In her later years, Harriet became a nurse, scout, and spy during the Civil War, aged 41, working for the Union Army, and is widely considered to be the first African American woman to serve in the military. Thanks to her expertise in scouting and planning, she played a key role in a single military raid that freed around 700 enslaved people in one night.

After the war, she settled in Auburn, New York, and despite battling chronic health issues from a childhood head injury inflicted by an overseer, and having very little money, Harriet opened a care home for elderly and sick Black Americans when she was 74.

She also threw her support behind the women’s suffrage movement, sharing stages with the likes of Susan B. Anthony. Harriet Tubman didn’t just fight for freedom; she lived it, breathed it, and extended it to everyone she could reach.

Empress Suiko

At 39, Suiko became Japan’s first female ruler, a bold and unprecedented move for the 6th century, but it was in the next two decades of her life that she truly came into her own.

With her sharp-witted nephew, Prince Shōtoku, acting as regent, Suiko helped Japan officially embrace Buddhism, giving the country a new spiritual identity. She introduced the Chinese calendar, backed a more structured government, and supported the Seventeen Article Constitution, which is widely seen as one of Japan’s first moral and political codes for good leadership and harmony.

Her reign is remembered as one that brought peace by easing clan rivalries, progress through forward-thinking reforms, and a new sense of purpose as Japan began to unify. Ruling for over 35 years, Empress Suiko proved that midlife isn't the end of a story; it can be the most powerful chapter yet.

Anna Wintour

When Anna Wintour took over as editor-in-chief of Vogue in 1988, aged 38, she wasted no time shaking things up, wielding an influence that became legendary. Her “mass with class” mantra captured her belief that high fashion should be aspirational, but also accessible, culturally relevant, and connected to the real world, resulting in figures like Kamala Harris and Greta Thunberg gracing the covers of Vogue’s international portfolio, blending glamour with substance.

Anna launched Teen Vogue, helped save struggling designers like John Galliano, and backed future stars like Alexander McQueen and Marc Jacobs. But perhaps her most dazzling legacy was transforming the Met Gala from a high-society dinner into the red-carpet event of the year; a spectacle so exclusive even A-listers aren’t guaranteed an invite.

She also helped launch the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund, nurturing a new generation of designers. And now, in her 70s, she’s still shaping the industry as Condé Nast’s global chief content officer, proof that a strong, visionary woman never goes out of style.

Clara Barton

In 1881, 59-year-old humanitarian Clara Barton founded the American Red Cross and led it for over two decades, expanding its mission beyond wartime relief to include responses to natural disasters at home and abroad.

She provided aid during major crises, including the Johnstown Flood (1889), the Russian famine (1892), and the Armenian massacres in the Ottoman Empire (1896). At a time when few women travelled internationally, Barton often journeyed independently to crisis zones, showing extraordinary resolve and courage. Her international efforts not only broadened the Red Cross’s reach but also set a powerful precedent for women in global humanitarian leadership.

Even after stepping down in her 80s, she founded the National First Aid Association of America in 1905, leaving a legacy that still shapes humanitarian aid today.

Margaret Thatcher

Love her or loathe her, Margaret Thatcher can’t be ignored in a conversation about women who changed the world later in life. Becoming the UK’s first female Prime Minister at 53, Margaret served for over 11 years, longer than any other 20th-century PM.

In her 50s and 60s, she led sweeping economic reforms: privatising major industries, deregulating financial markets, and introducing the “Right to Buy” scheme, which gave council tenants the chance to purchase their homes.

Supporters praised her for boosting the economy and reducing union power; critics pointed to rising inequality and lasting damage to industrial communities. On the global stage, she led Britain to victory in the Falklands War and played a supporting role in Cold War diplomacy. Divisive, yes, but Thatcher proved that political power knows no age or gender limits.

Queen Victoria

In her autumn and winter years, Queen Victoria oversaw the expansion of the British Empire to become the largest in history, with territories spanning every inhabited continent, and at 58, was crowned Empress of India, a title that cemented her role as figurehead of a global superpower.

Her reign coincided with a period of rapid industrial, scientific, and cultural progress known as the Victorian era, a time that not only shaped Britain and influenced the wider world but also saw pioneering women step into the spotlight.

Angela Burdett-Coutts co-founded the RSPCA and, in her 60s, helped launch the NSPCC. Josephine Butler fearlessly challenged the Contagious Diseases Acts in her 40s (laws that allowed women merely suspected of prostitution to be forcibly examined and detained), with her campaign leading to their repeal in 1886, marking a landmark victory for women's rights.

Elizabeth Fry, the “Angel of Prisons”, made her biggest impact in her 40s and 50s, advocating for humane treatment and education for female prisoners, which led to major reform and the 1823 Gaols Act. Meanwhile, in America, Nellie Bly made her name as a daring journalist and continued championing social reform well into her 40s and beyond, reporting from World War I and fighting for workers’ rights and adoption reform.

Eleanor of Aquatine

Living to 82 in the 12th century? That’s impressive enough, but Eleanor of Aquitaine didn’t just survive; she thrived in her later years.

Nearly kidnapped for her lands as a young widow, she went on to marry two kings, bear ten children, and help govern both France and England. After supporting her sons in a rebellion against their father, Henry II, he had her imprisoned for 16 years. But Eleanor bounced back.

Freed at 65 when her son Richard the Lionheart became king, she ruled as regent while he went on Crusade, during which time she successfully negotiated ransoms, quashed rebellions, and ran the country with sharp political savvy. And she didn’t stop there.

Into her 80s, she was still pulling strings in Aquitaine, proving age was no barrier to power. She also helped shape medieval culture as a patron of troubadours (wandering musicians who sang of love and honour), popularising the ideals of chivalry and courtly love that echo through romance to this day.

Maya Angelou

Poet, author, performer and activist, Maya Angelou may be well known for her powerful memoir I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, a groundbreaking book that gave voice to Black womanhood, trauma, and resilience, which she published when she was 41, but the best was yet to come.

At 65, she was invited by President Bill Clinton to read her poem On the Pulse of Morning at his 1993 inauguration, becoming only the second poet in U.S. history to do so. At 70, she made her directorial debut with the film Down in the Delta.

And at 83, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honour. And that’s not all! She scooped up three Grammy Awards for her spoken word albums, inspired generations with her wisdom and wit, and became a professor of American Studies at Wake Forest University in North Carolina. Through it all, she showed us how to rise above life’s trials, as she once wrote, “You may not control all the events that happen to you, but you can decide not to be reduced by them.”

Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut, the queen who would be king, didn’t just break a glass ceiling; she shattered a stone one! Born around 1504 B.C.E., she was never meant to rule Egypt, but when her husband (and half-brother) Thutmose II died and his toddler son became pharaoh, Hatshepsut stepped in as regent, until she boldly declared herself co-ruler and took on the full title of pharaoh.

To ensure she enjoyed the same respect given to a male ruler, Hatshepsut often presented herself as a king, donning traditional regalia and a false beard. Her reign, which lasted over two decades, running into her late forties, brought prosperity, stability, and spectacular architectural achievements.

Notably, she opened a hugely successful trade route with the then-mysterious land of Punt (believed to be modern-day Eritrea), bringing back riches that funded temples, monuments, and towering obelisks, including her magnificent mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari, where she was eventually buried. Though later rulers tried to erase her from history, archaeologists rediscovered her legacy centuries later. Today, she’s rightly recognised as one of Egypt’s most visionary and successful pharaohs.

Queen Elizabeth II

Queen Elizabeth II dedicated her entire life to serving her country and her people, ascending the throne at just 25, but many of her most remarkable contributions unfolded later in life.

At 60, she became the first British monarch to visit China, strengthening diplomatic ties. At 70, she helped modernise the monarchy by approving the royal family’s website, and at 85, she made a historic reconciliation visit to Ireland, making her the first UK monarch to visit the independent country in 2011.

Even in her 90s, she remained a symbol of stability and compassion, as her speech during the COVID-19 pandemic at age 93 was watched by over 24 million people, appreciative of the reassurance.

Supporting causes related to health, education, wildlife, and the arts, Queen Elizabeth II was patron to over 600 charities and organisations, which was more than any other royal in history, what’s more her influence is said to have helped raise over a billion pounds for charity, touching the lives of millions across the UK and Commonwealth.

More than anything, her legacy is one of lifelong service, quiet diplomacy, and unwavering devotion to the people she served, reigning for an extraordinary 70 years and 214 days, making her the longest of any British monarch, providing continuity and stability through decades of global change.

Sirimavo Bandaranaike

After the assassination of her husband, Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike in 1959, Sirimavo Bandaranaike entered politics and, at 44, became the world’s first female Prime Minister, leading Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) from 1960.

In her 50s, she nationalised major industries, including banking, insurance, and oil, to reduce foreign control and promote economic self-reliance. In 1972, she made the country a republic, cutting ties with the British monarchy and officially renaming it Sri Lanka.

At 60, she chaired the Non-Aligned Movement summit, giving a voice to developing nations. Despite political setbacks, she returned to power at 78, serving until her death at 84, leaving a legacy of resilience and pioneering leadership.

Mária Telkes

A trailblazing scientist who moved to the U.S. from Hungary, Mária Telkes was a physical chemist with a flair for invention. Although she rose to fame early in her career for developing a solar-powered water distiller used during World War II, it was in her midlife and beyond that she truly began to shine.

At 48, she teamed up with architect Eleanor Raymond to create the Dover Sun House, one of the first homes heated entirely by solar energy, with her use of Glauber’s salt to store heat hailed as a breakthrough in thermal energy storage.

At 53, she built a solar oven that could reach 200°C, which was perfect for use in remote communities, while in her 70s, she helped create the world’s first solar-electric residence, known as The Carlisle House, in Massachusetts in 1980.

What’s more, throughout her glittering career, Mária secured over 20 patents related to solar energy, which helped to lay the groundwork for modern solar technology, and earned her the affectionate moniker the "Sun Queen".

Natalie Denton is a freelance writer and editor with nearly 20 years of experience in both print and digital media. She’s written about everything from photography and travel, to health and lifestyle, with bylines in Psychologies, Women’s Health, and Cosmopolitan Hair & Beauty. She’s also contributed to countless best-selling bookazines, including Healthy Eating, The Complete Guide to Slow Living, and The Anti-Anxiety Handbook.