Sign up to our free daily email for the latest royal and entertainment news, interesting opinion, expert advice on styling and beauty trends, and no-nonsense guides to the health and wellness questions you want answered.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

woman&home Daily

Get all the latest beauty, fashion, home, health and wellbeing advice and trends, plus all the latest celebrity news and more.

Monthly

woman&home Royal Report

Get all the latest news from the Palace, including in-depth analysis, the best in royal fashion, and upcoming events from our royal experts.

Monthly

woman&home Book Club

Foster your love of reading with our all-new online book club, filled with editor picks, author insights and much more.

Monthly

woman&home Cosmic Report

Astrologer Kirsty Gallagher explores key astrological transits and themes, meditations, practices and crystals to help navigate the weeks ahead.

The 1960s were a memorable and transformative decade for cinema. The collapse of the old Hollywood studio system in the mid-60s paved the way for a bold new era of cinema, heavily shaped by international influences and defined by more experimental, daring techniques and innovative use of music.

This shift marked the start of the ‘New Hollywood’ movement, which ran from the mid-60s through until the early 80s. A new generation of trailblazing filmmakers emerged, including Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Mike Nichols, John Schlesinger, Arthur Penn, Sidney Lumet, and so many more. Some of the most exciting films were released at the conception of the movement in the 60s, like Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate and Easy Rider.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, the French New Wave, which started in the late 50s, was still creating ripples throughout the 60s while Kitchen Sink realism was still in full swing in the UK.

Here, we look at the best films from the era, with a mixture of star-studded old Hollywood flicks to the more progressive films released towards the end of the decade, as well as European arthouse choices and gritty British releases.

The best films of the 1960s

Midnight Cowboy, John Schlesinger (1969)

Adapted by screenwriter Waldo Salt from the novel by James Leo Herlihy, Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy follows naive Texan cowboy Joe Buck (played by Jon Voight) as he moves to New York to become a gigolo. He sparks up an unlikely friendship with another hustler, Ratso (Dustin Hoffman), who sits at the fringes of society, and the pair navigate the unforgiving city together.

At its core, it's a buddy film, but it’s so much more, covering themes of loneliness, friendship, the myth of the American dream, repressed homosexuality, and alienation.

Book of Movies: The Essential 1,000 Films to See | £27.85 at Amazon

The perfect gift for any cinephile friends, this comprehensive book from the New York Times brings together the top 1,000 films of all time. Packed with critiques, reviews and information about where to find the films, it's a treasure trove for any film buff.

The Graduate, Mike Nichols (1967)

The Graduate, soundtracked by Simon & Garfunkel, follows Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman), a recent college graduate who’s struggling to find meaning in his life or a way forward. He embarks on an affair with the older Mrs Robinson (Anne Bancroft) but also falls for her daughter. Perhaps what’s most radical about the film, though, was director Mike Nichols’s decision to use previously unreleased songs from Simon & Garfunkel for the soundtrack, with the folky songs driving the narrative, so much so that ‘The Sound of Silence’ and ‘Mrs Robinson’ are synonymous with the 1967 classic.

Sign up to our free daily email for the latest royal and entertainment news, interesting opinion, expert advice on styling and beauty trends, and no-nonsense guides to the health and wellness questions you want answered.

Before this, Hollywood films used traditional orchestral film scores in film as a background device; using popular music as an important narrative feature was a radical approach, deepening the sense of disillusionment, desire and loneliness that underpinned the film.

Breathless, Jean-Luc Godard (1960)

Possibly the coolest film ever, Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (À bout de souffle) follows Parisian criminal Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and his doomed relationship with aspiring journalist Patricia Franchini (Jean Seberg), whom he turns to after killing a policeman. On the surface, it’s a crime drama, but what made this film so radical was its unconventional approach to filmmaking and editing techniques.

Featuring extreme jump cuts, naturalistic speech, dismantling of the fourth wall and a fragmented narrative structure that challenged norms of storytelling, this seminal film is not only one of the best French New Wave films but an all-time great.

2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick (1968)

This experimental film from director Stanley Kubrick and screenwriter Arthur C. Clarke didn’t open to immediate acclaim, initially being met with harsh criticism and general confusion. So much so that Kubrick cut the film from its original 161-minute duration to 142. While the film’s pioneering special effects were praised, viewers were confused by the sparse dialogue, slow pace and long scenes only accompanied by music. Rather than a high-drama sci-fi film about extraterrestrial life, it offered a philosophical exploration of the promise and pitfalls of space travel.

Rosemary's Baby, Roman Polanski (1968)

Faithfully adapted from Ira Levin’s best-selling book, Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby transcended genres, blending psychological horror, occult cinema and dark humour. It also catapulted Mia Farrow to fame in her role as a paranoid young mother-to-be who grows suspicious of her husband (John Cassavetes) and eccentric neighbours (played by Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer), suspecting they are hatching a satanic plot against her.

Her pregnancy - and everything around them - takes a dark turn, with viewers not always sure what events are real and which are the result of Rosemary’s paranoia.

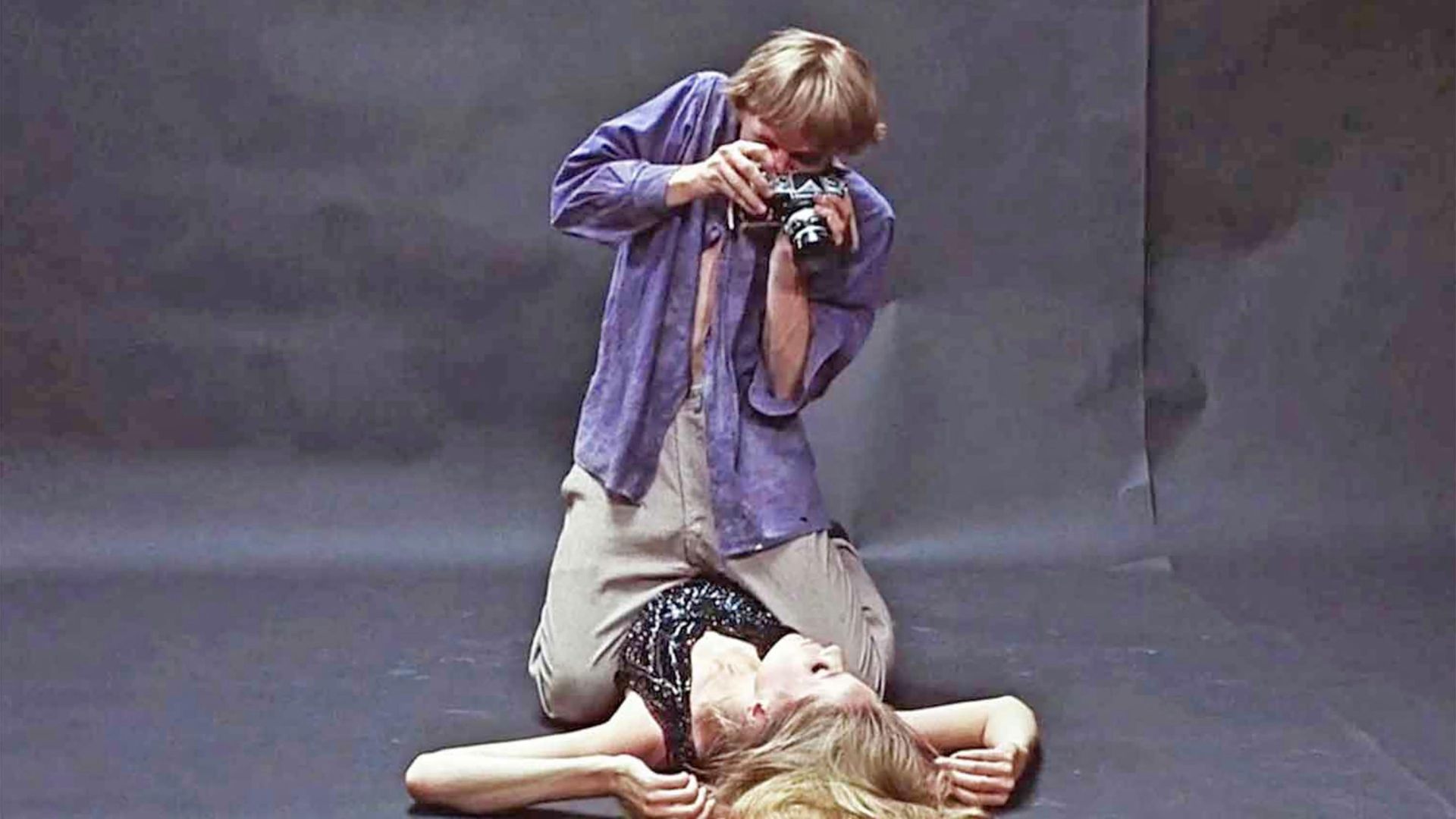

Blow-Up, Michelangelo Antonioni (1966)

Michelangelo Antonioni’s Palme d’Or-winning film, set in 60s London, follows hedonistic fashion photographer Thomas (David Hemmings), who snaps two lovers in a public park, only to discover he’s unwittingly captured evidence of a murder in one of the photos. A stylish and thought-provoking film that explores the contrast between reality and illusion, it’s also an enjoyable time capsule of the swinging 60s.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

Kubrick’s darkly comedic political satire, Dr. Strangelove, may have been released over 60 years ago, but this razor-sharp nuclear war comedy, which essentially asks the question of what would happen if the wrong person pushed the wrong button, still resonates today.

8½, Federico Fellini (1963)

“8½ is the best film ever made about filmmaking,” claimed the late critic Roger Ebert, in 2000 - a statement that still holds today. The title is a witty reference to Fellini’s career as the film was his ‘eighth-and-a-half’ following seven features and two short segments. The film, which weaves in and out of reality, follows a director who finds himself hopelessly lost in a creative block. Outwardly (in both manner and style) cool but plagued with inner turmoil, Guido (played by Marcello Mastroianni) is a stand-in for Fellini himself.

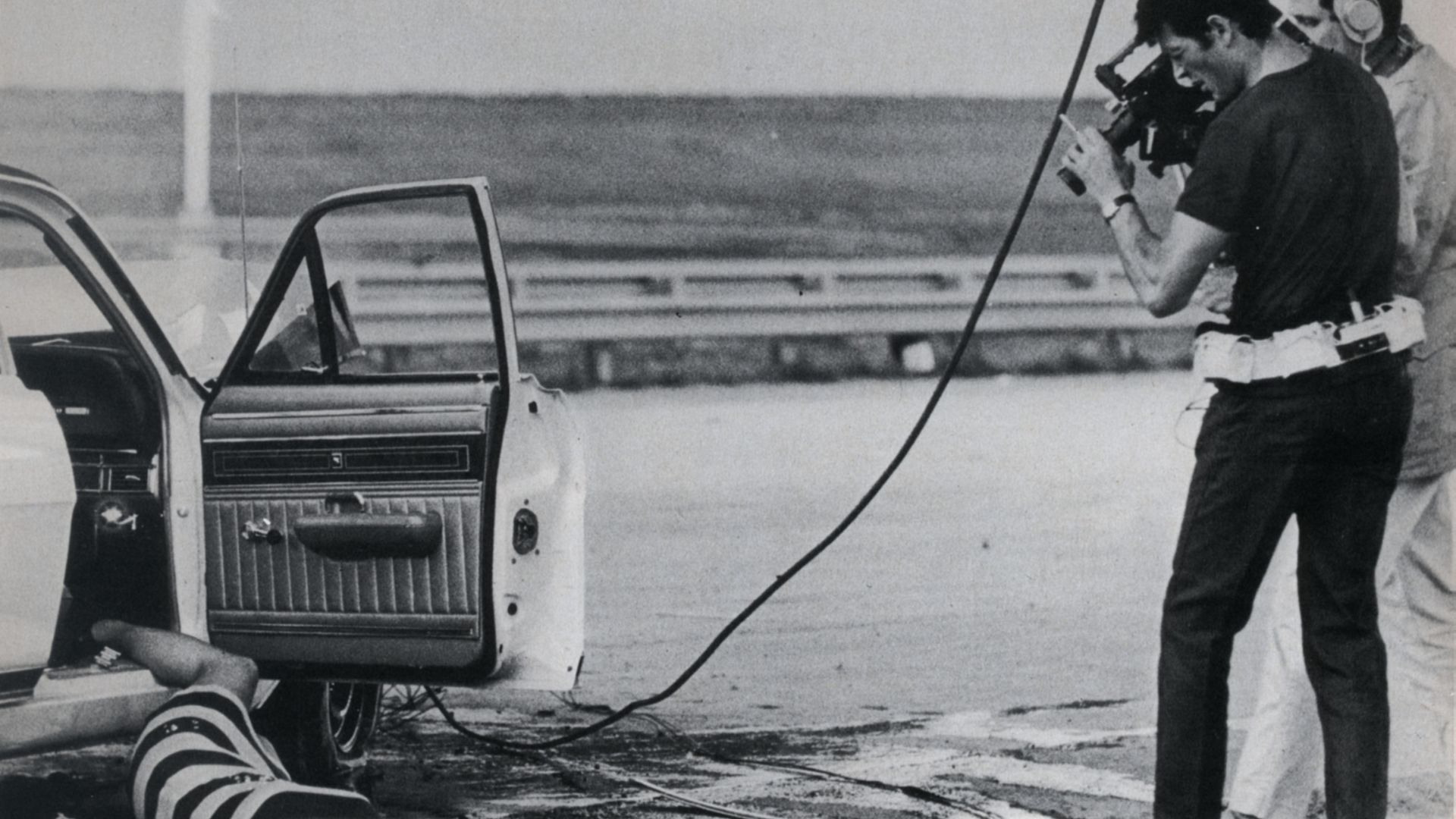

Medium Cool, Haskell Wexler (1969)

Haskell Wexler’s debut feature blends fictional storytelling and documentary techniques, following the life of a hardened and detached TV cameraman, John Cassellis (played by Robert Forster), as he covers the violent riots surrounding the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

An examination of journalism ethics, race relationships and corruption, Medium Cool also leaves viewers thinking about their complicity and role in deciphering the ‘truth’ behind the story.

Easy Rider, Dennis Hopper (1969)

One of the best-ever road movies, Easy Rider follows two bikers on their way from LA to Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Soundtracked by rock classics from Steppenwolf, The Byrds and Jimi Hendrix, the characters of Wyatt (Peter Fonda) and Billy (Dennis Hopper) zip through the open roads of America, meeting an array of eccentric characters on the road, representing the different facets of American society at the time.

Rebellious, idealistic and melancholic all in one, it’s one of the last great films of the decade.

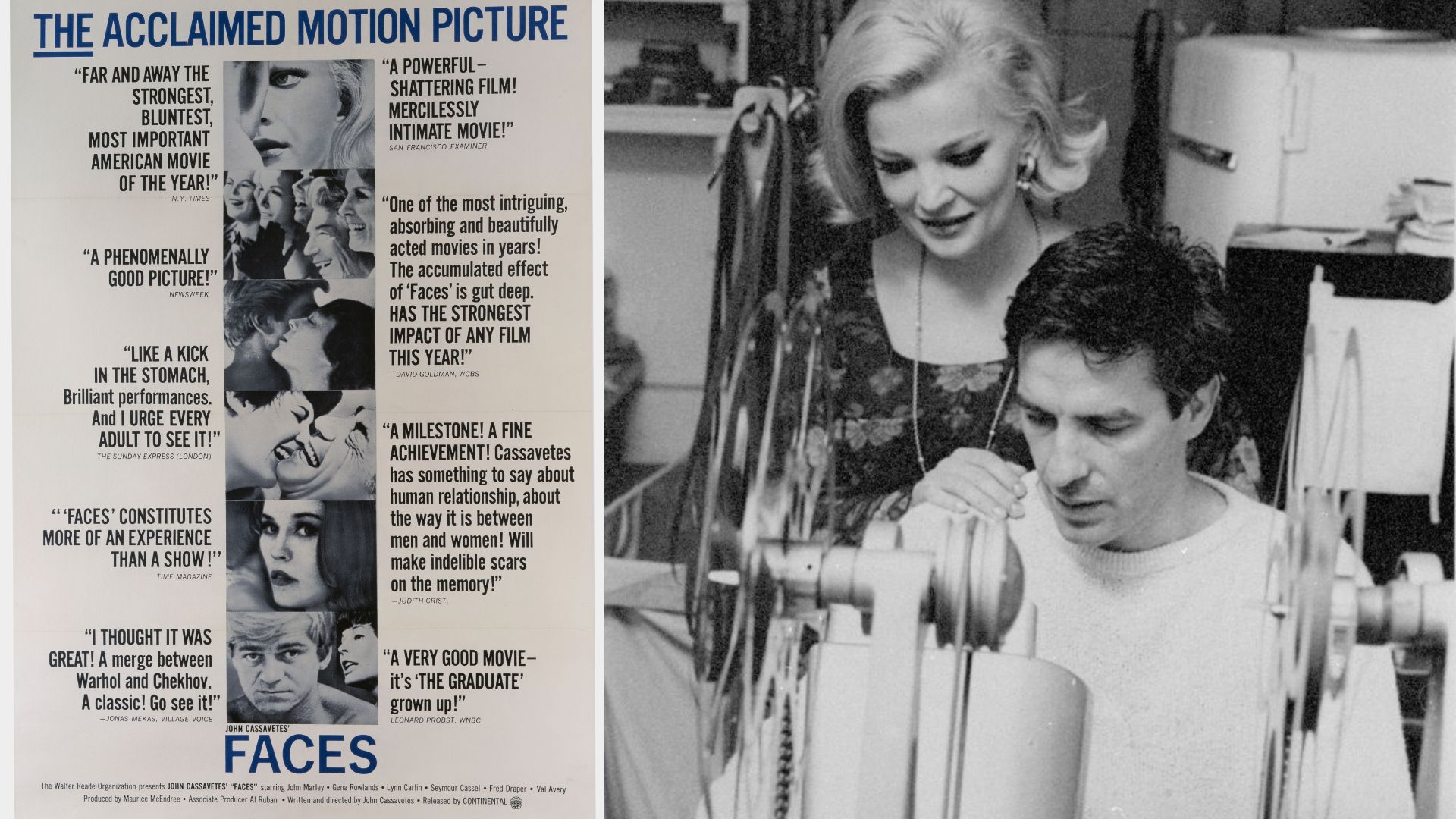

Faces, John Cassavetes (1968)

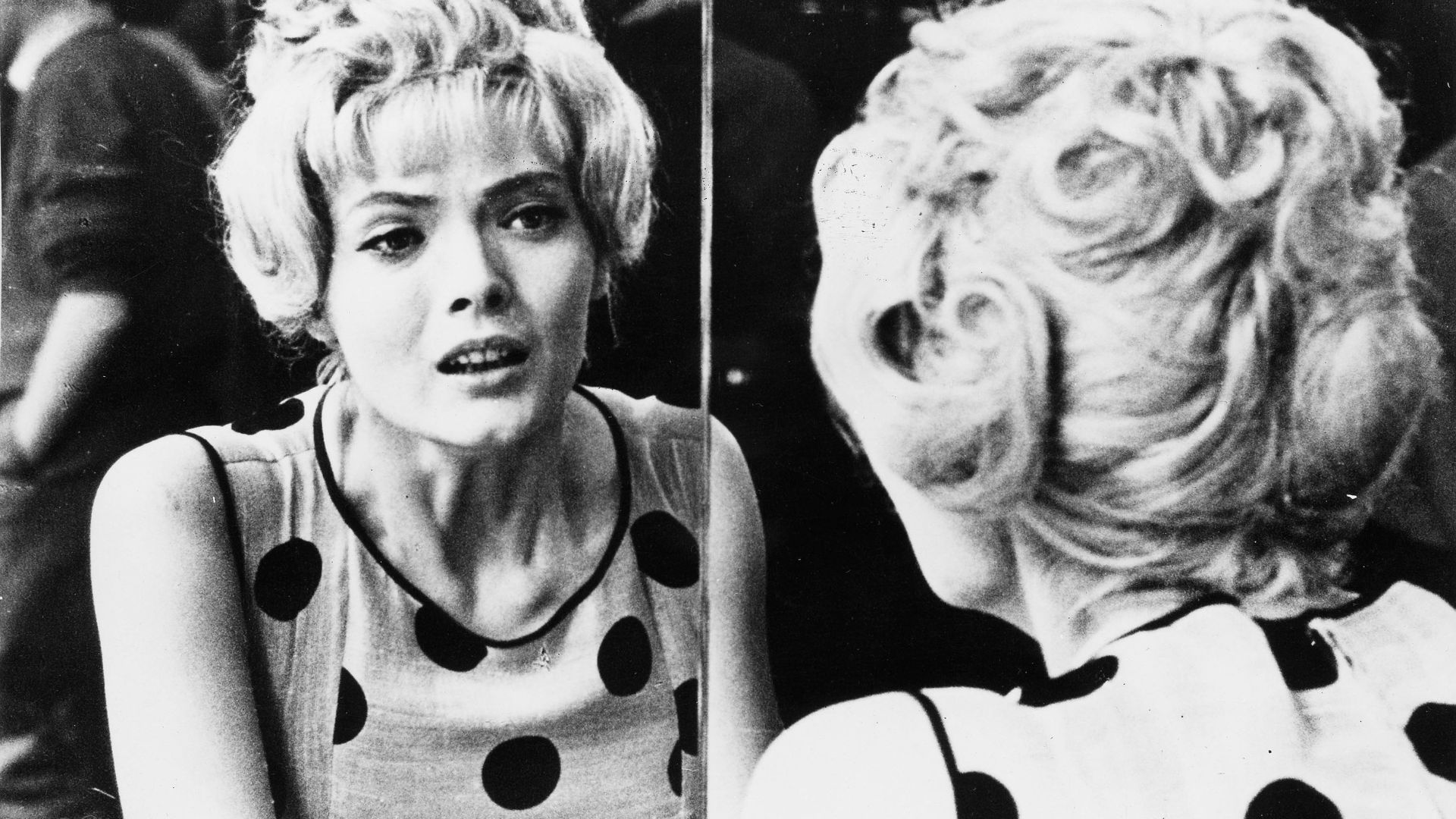

Written, directed and produced by John Cassavetes, Faces tracks the breakdown of a middle-aged couple’s marriage (played by John Marley and newcomer Lynn Carlin). Shot and edited in his own house, Cassavetes also featured his friends and go-to cast members, including Gena Rowlands (pictured) and Seymour Cassel. Shot on grainy 16mm film in an improvisational cinema-verite style, the DIY aesthetic offered an intimate portrait of its protagonists.

Kes, Ken Loach (1969)

The poignant coming-of-age story of northern schoolboy, Billy Casper (David Bradley) and his pet kestrel, Kes remains one of Ken Loach’s most celebrated films. Aired locally in 1969, the film went on wide release in 1970.

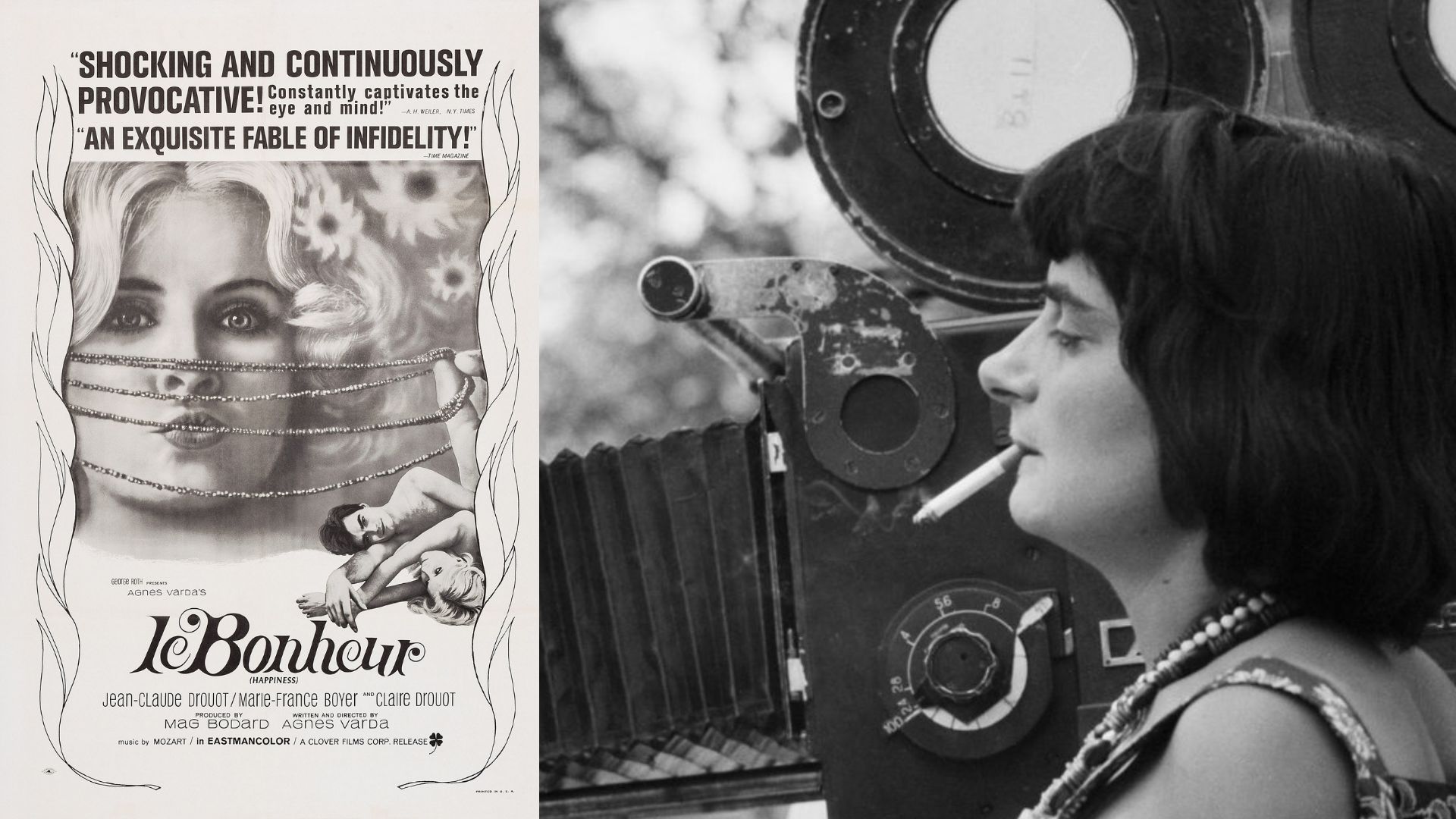

Cléo from 5 to 7, Agnès Varda (1962)

It’s no secret that the film industry is heavily male-dominated, and in the 1960s, even fewer female directors managed to break through. Outside of Hollywood, there was slightly more diversity, with Agnès Varda spearheading the French New Wave movement along with Godard, Truffaut and others. And, Cléo from 5 to 7 (Cléo de 5 à 7) is one of her best.

Eternally cool, the film follows singer Cléo in real time as she waits for the results of a biopsy, traversing through the streets of Paris, trying on clothes, sipping on brandy and catching cabs. It’s succinct, elegant and melancholic, as the protagonist questions her own mortality while going around her day-to-day life.

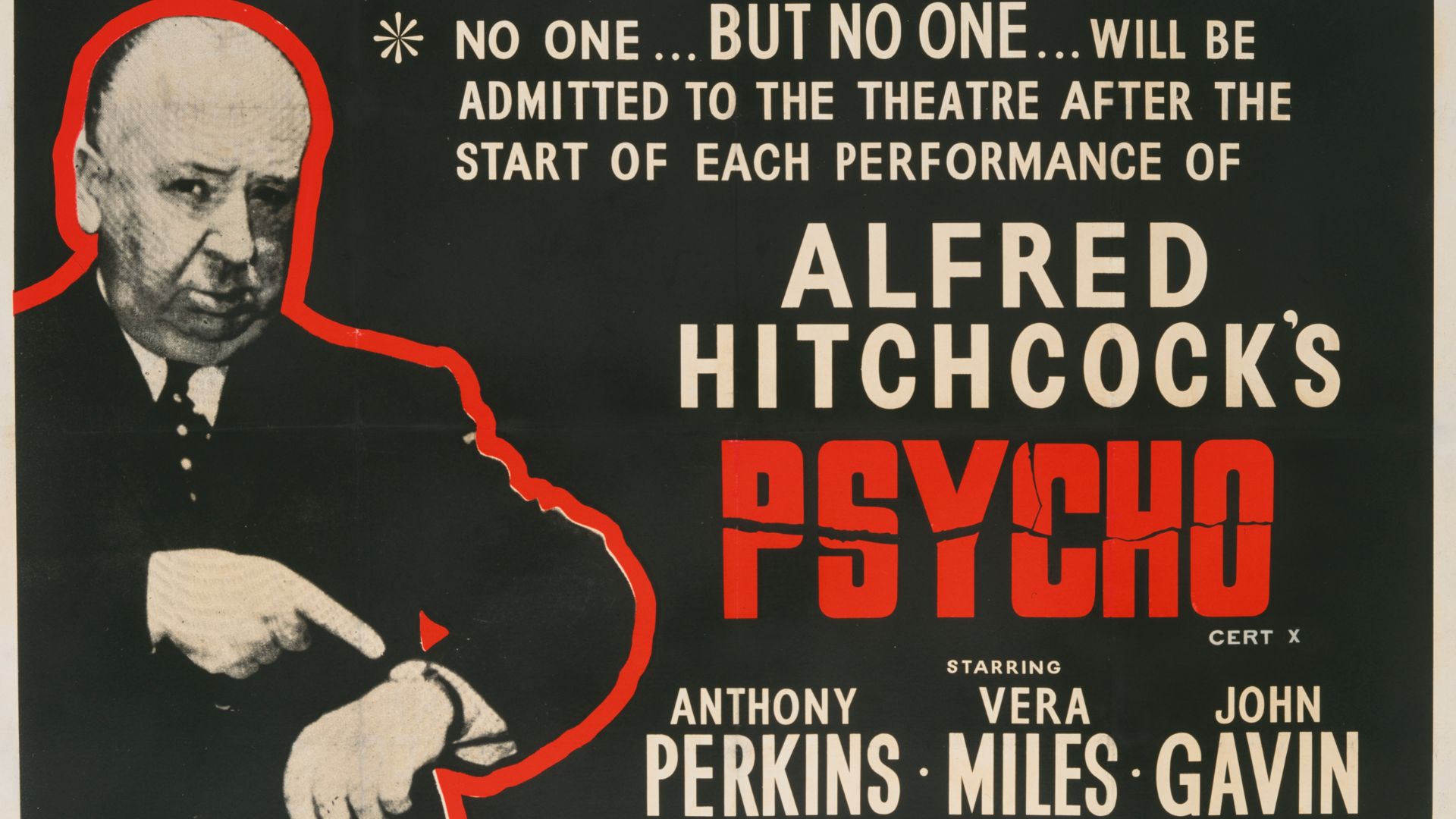

Psycho, Alfred Hitchcock (1960)

Arguably one of Alfred Hitchcock’s most influential works, Psycho is widely considered one of the best horror films ever made.

It stars Janet Leigh as Marion Crane, a secretary from Phoenix who flees after stealing her employer’s money. When she stops at a remote motel for the night, she discovers its seemingly innocent owner, Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), is far from what he seems. A seminal film that redefined the slasher genre, it also has one of the most famous plot twists in film history.

The Innocents, Jack Clayton (1961)

Jack Clayton’s 1961 masterpiece, The Innocents, is a complex psychological drama that still chills today. Adapted from Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, Deborah Kerr plays a woman who takes a governess job, caring for two children in an English manor. All is well initially, but she starts to fear the estate is haunted by ghosts and that the children are possessed.

Weekend, Jean-Luc Godard (1967)

Weekend isn’t a film with mass appeal. In fact, some parts of it are undeniably difficult to watch - like a seven-minute-long take of a traffic jam that feels almost as frustrating to watch as it is to experience in real life. But it’s also a highly rewarding viewing experience.

A stylish satire of the French bourgeoisie, featuring absurd humour and experimental, fragmented film-making, the framework of the film centres around a married middle-class couple heading on a road trip to kill the wife’s parents for their inheritance.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Blake Edwards (1961)

Edwards’s adaptation of Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s, released at the beginning of the decade, is unashamedly old Hollywood. Dripping in glamour, Audrey Hepburn plays the charming socialite Holly Golightly, decked in an iconic LBD, who finds herself drawn to an aspiring writer (played by George Peppard) who moves into her upscale apartment block.

To Kill a Mockingbird, Robert Mulligan (1962)

Based on the award-winning Harper Lee novel, To Kill a Mockingbird achieved the almost impossible task of doing justice to its source material. Six-year-old Scout (Mary Badham) watches her father, Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck), defend the falsely accused African American Tom Robinson (Brock Peters) against the backdrop of a racist and highly segregated America.

Persona, Ingmar Bergman (1963)

Dream-like, cryptic and sensual, Persona is one of Swedish director Ingmar Bergman’s best. Liv Ullmann plays a newly-mute stage actress, Elisabet, who is cared for by a young nurse, Alma (played by Bibi Andersson). She remains speechless while Alma speaks, with the two women eventually converging as they undergo a spiritual and emotional transference. Beguiling and beautiful, Persona is one of the best experimental films of the era.

Eyes Without a Face, Georges Franju, (1960)

Georges Franju’s visceral horror film, Eyes Without a Face (Les yeux sans visage), was initially met with a mixed critical reception. Telling the tale of noted doctor, Dr Génessier (Pierre Brasseur), who seeks out corpses whose faces he can use to reconstruct the face of his daughter, it’s perhaps not surprising that not everyone loved the macabre film. So, why watch it? It’s beautifully shot, far less gory than it sounds and blends film noir with psychological horror.

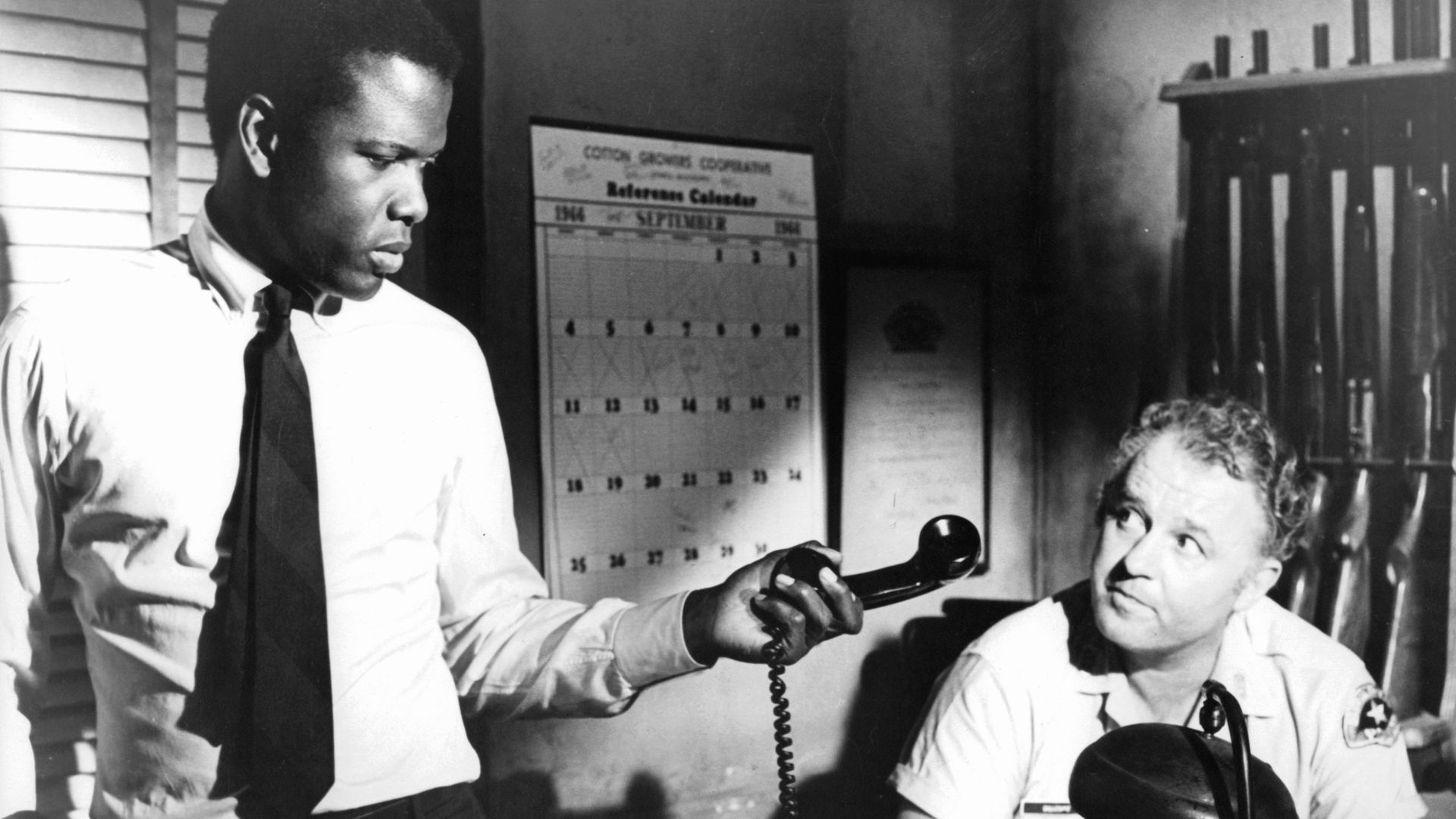

In The Heat of The Night, Norman Jewison (1967)

Norman Jewison’s Oscar-winning detective drama investigates racial conflict and prejudice in the Deep South. Telling the story of African American Philadelphia cop Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier), who is arrested for murder by Gill Gillespie (Rod Steiger), a police chief in the small fictional town of Sparta, the pair eventually join forces to find the real murderer.

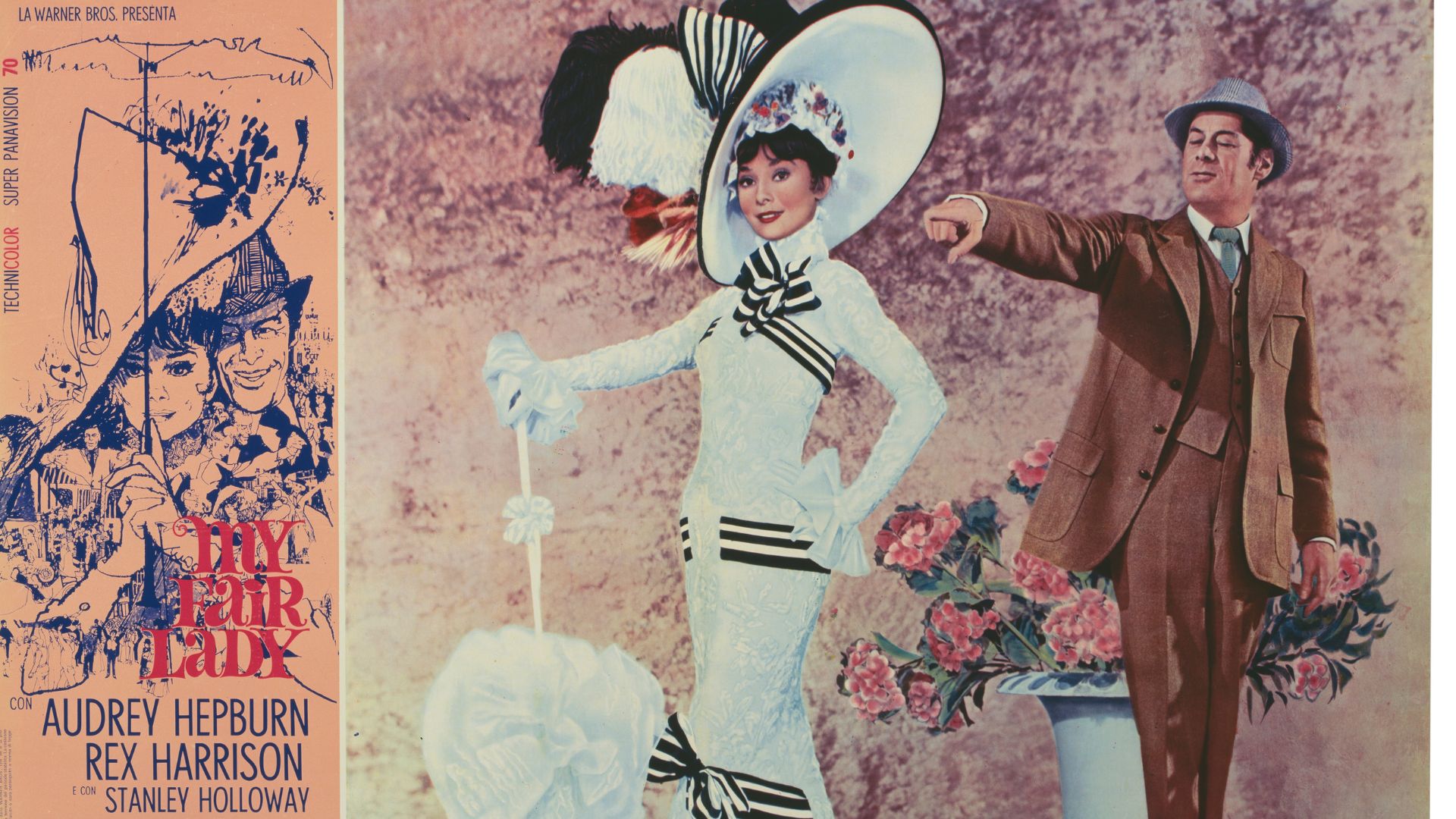

My Fair Lady, George Cukor (1964)

My Fair Lady was one of the last ‘Golden Age’ Hollywood musicals, embodying the big, lavish Hollywood productions and the Old Hollywood studio system, which had eroded by the end of the decade.

In it, Audrey Hepburn plays a plucky cockney girl, Eliza Doolittle, who is transformed into a genteel “lady” by snobby phonetics professor Henry Higgins (played by Rex Harrison). Based on George Bernard Shaw's 1913 stage play Pygmalion, it was a popular and critical success and remains a fun sing-along classic.

Bonnie & Clyde, Arthur Penn (1967)

Romantic, rebellious, funny, cruel and heartbreaking, Bonnie & Clyde has it all. Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway star as the bank-robbing duo on a crime spree before it all comes to an end in the film’s famous final scenes.

The impact of Penn’s film is profound, mostly due to its revolutionary depiction of graphic violence on screen, paving the way for films like The Godfather, True Romance and countless others.

Night of the Living Dead, George A. Romero (1968)

A landmark horror movie, Night of the Living Dead was reportedly rejected by several studios but remains a cult-favourite to this day. Not quite the first zombie film ever made, but definitely one of the most influential, Romero’s allegory-laden, low-budget flick follows a group of seven unsuspecting people who become trapped in an old farmhouse, chased by flesh-eating ghouls.

The Manchurian Candidate, John Frankenheimer (1962)

John Frankenheimer’s paranoid thriller, based on the Richard Condon novel of the same name, was highly controversial, even being pulled in the US after its initial run and banned in Eastern European countries then under Communist governments (per Washington Post).

Set in the early fifties during the Korean War, it centres around a platoon of US soldiers who are captured and brainwashed by international Communist forces. US Army Sergeant Raymond Shaw (played by Laurence Harvey) is brainwashed into becoming a sleeper assassin; a plot that’s slowly uncovered by fellow P.O.W. Major Bennett Marco, played by Frank Sinatra.

Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel (1967)

Buñuel’s sensual classic follows frustrated housewife Séverine, who takes on a double life under the name of Belle de Jour while her loving but dull husband is away at work.

Daisies, Věra Chytilová (1966)

Directed by female Czech filmmaker Věra Chytilová, Daisies is an anarchic, defiant film that follows two hedonistic teens, both named Marie (played by Ivana Karbanová and Jitka Cerhová), who pull off a series of rebellious pranks.

“If everything’s going bad…we’re going bad as well” decide the protagonists in a pivotal scene, kickstarting their spree of “bad” behaviour.

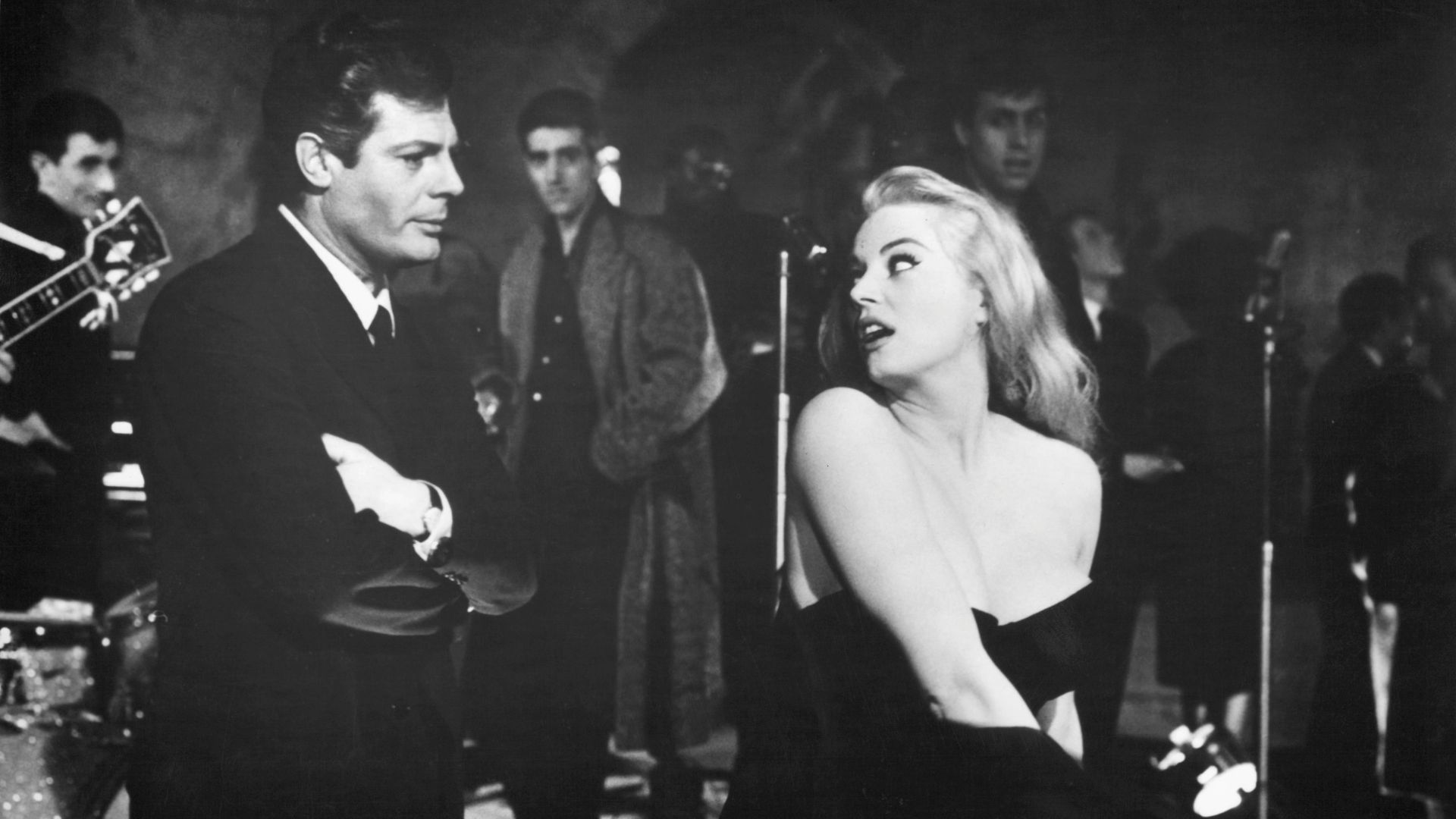

La Dolce Vita, Federico Fellini (1960)

La Dolce Vita skyrocketed auteur Fellini to international success, as audiences all over the world were seduced by its captivating cinematography, slick suits and cool, glamorous characters. The character of tabloid journalist Marcello Mastroianni flits between parties, women and the general excesses of 1960s Rome, struggling to reconcile his draw to the hedonistic world occupied by the elite with his (more meaningful) literary ambitions.

Last Year in Marienbad, Alain Resnais (1961)

A hypnotic film set in a palatial chateau, at its core, Last Year in Marienbad centres on a handsome man X (Giorgio Albertazzi)’s insistence that he had a romantic entanglement with a beautiful woman, A (Delphine Seyrig). She claims never to have met him. So, which nameless character is telling the truth?

Covering themes of memory, time and identity, once you stop trying to find a solution in this visually arresting French New Wave classic, then you can start to enjoy it.

Le Bonheur, Agnès Varda (1965)

Le Bonheur (Happiness) charts a young couple’s seemingly happy and uncomplicated marriage - that is, until the man falls in love with another woman. Varda used actor Jean-Claude Drouot and his real wife and children in this abstract classic that covers love, fidelity, and the illusion of happiness.

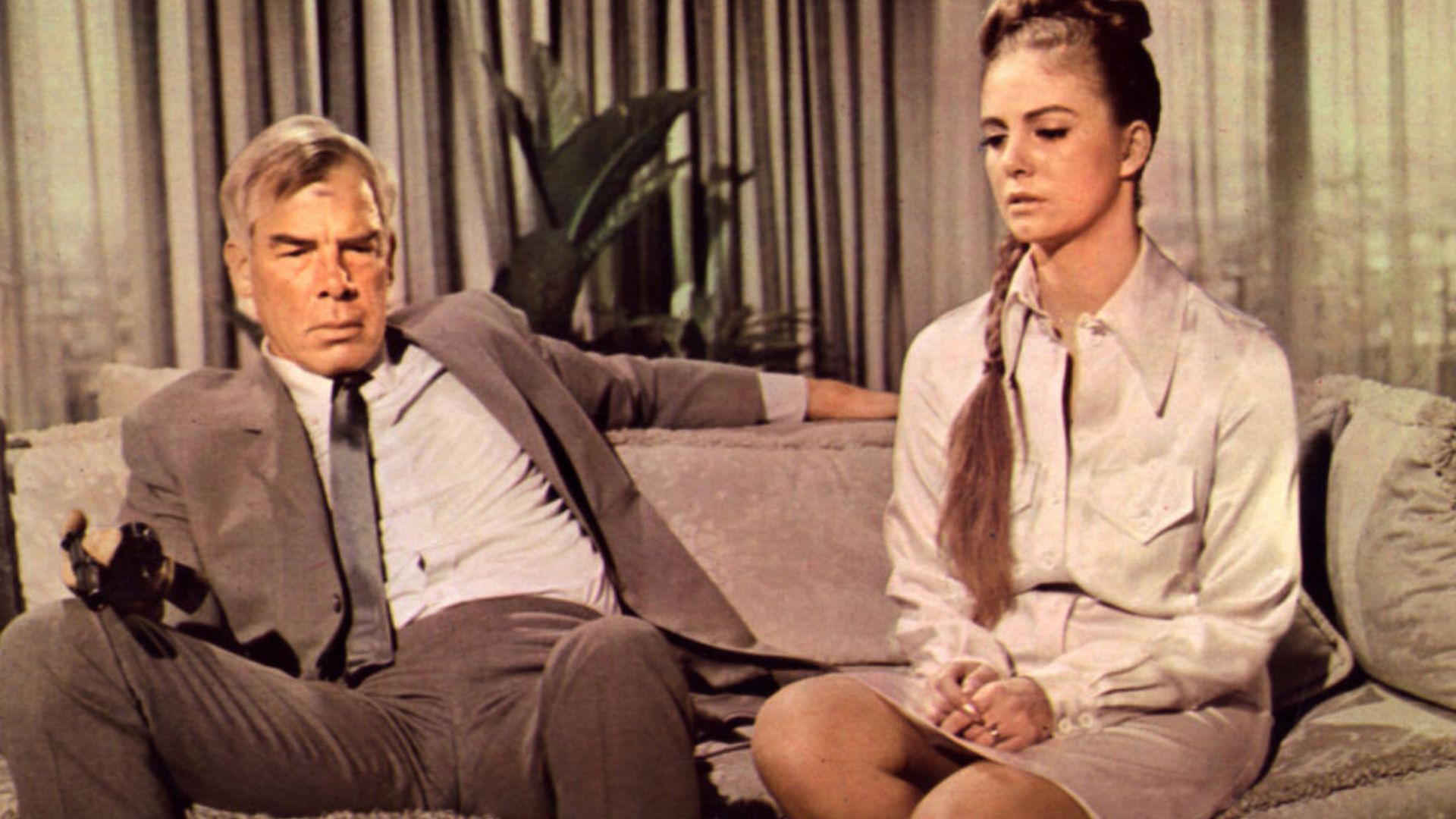

Point Blank, John Boorman (1967)

After being double-crossed and left for dead on Alcatraz Island by his partner, protagonist Walker (Lee Marvin) returns years later to get his revenge. Boorman’s experimental revenge thriller is gritty, surrealist and disorientating - and well worth a watch.

The Sound of Music, Robert Wise (1965)

It might not be the most popular film of the decade for cinephiles, but there is no denying the enduring appeal of Robert Wise’s The Sound of Music. Adapted from the hit Broadway musical of the same name, it centres around a young woman, Maria von Trapp (Julie Andrews), who leaves an Austrian convent to become a governess to seven children.

The story is largely historically inaccurate, marred with controversy over its oversimplification of the threat (and impact) of Nazism in Austria. It’s flawed, but it remains a cultural artefact, regularly referenced in pop culture to this day.

Anna is an editor and journalist with over a decade of experience in digital content production, ranging from working in busy newsrooms and advertising agencies to fashion houses and luxury drinks brands. Now a freelance writer and editor, Anna covers everything lifestyle, from fashion and skincare to mental health and the best cocktails (and where to drink them).

Originally from Glasgow, Anna has lived in Berlin, Barcelona, and London, with stints in Guernsey and Athens. Her love of travel influences her work, whether she’s stocking up on the best skincare at French pharmacies, taking notes on local street style, or learning to cook regional cuisines. A certified cinephile, when she's not travelling the world, you'll find her hiding away from it at her local cinema.