Eat like a royal – discover the vintage mealtime rituals enjoyed by the aristocracy over the years

We dig into the elaborate and bizarre etiquette rules upheld by high society through history

Think you know fancy dining? Think again. From Tudor showstoppers like gold-dusted peacock to Georgian banquets featuring trumpeters, toastmasters, and up to 96 dishes at once, history’s upper crust weren’t just served dinner, they were treated to a full-blown spectacle!

But with great grandeur came great expectations. These meals were governed by strict rituals and silent rules that the elite quite literally lived and dined by. Victorian ladies sipped soup without a sound, footmen moved with choreographed precision, and heaven forbid you crossed your knives or applauded the after-dinner harpist.

Across centuries of high society, mealtimes were more than meals; they were performances. And the price of a misstep? Social exile. So read on to discover all the do’s and don’ts of dining like a duchess from days gone by…

The wildest aristocratic mealtime rituals from days gone by

Sweet spectacles

Known as subtleties, ornate and lavishly decorated sugar sculptures wowed and tantalised guests at medieval, Tudor, and Renaissance banquets. These elaborate edible artworks, shaped into awe-inspiring spectacles like castles, mythical beasts, or coats of arms, were paraded between courses to entertain and astonish.

In an age when sugar was more precious than gold, these creations weren’t just to satisfy guests’ sweet-tooths; they were declarations of status, artistry, and intellect.

A feast of feathers

At royal feasts from the high medieval period through the Tudor, Stuart, and Renaissance eras, aristocrats served more than just dinner, they served theatre!

Forget meat and two veg: exotic birds like peacocks and swans were skinned, roasted, then redressed in their own dazzling feathers, sometimes even brushed with gold leaf, to shock and awe the assembled guests.

Sign up to our free daily email for the latest royal and entertainment news, interesting opinion, expert advice on styling and beauty trends, and no-nonsense guides to the health and wellness questions you want answered.

What’s more, in the most dramatic finales, live birds were reportedly even hidden inside pies, bursting out when the crust was cut, a spectacle thought to have inspired the popular nursery rhyme.

Etiquette or exile

Edwardian dining rooms were minefields of social protocol, especially among the upper and aspiring middle classes, and it was surprisingly easy to be shunned over a dinner table.

Slurping soup, dipping bread, mishandling cutlery, or, heaven forbid, talking politics could mark you as uncouth. Even how you held your fork or when you spoke mattered.

This wasn’t just an Edwardian quirk, either, as these etiquette anxieties began in the Georgian era, flourished through the Victorians, and peaked in Edwardian society as the middle classes mimicked aristocratic ways.

One wrong move could cost you your reputation, invitations, and even marriage prospects.

Slurp and be shamed

In Victorian England, even how you ate soup had rules. Well-to-do diners were expected to move their spoon away from themselves, rather than scooping them towards, as pulling food closer appeared greedy.

There was even a genteel rhyme to help children remember their manners: “Like ships that go out to sea, I push my spoon away from me.” Slurping, blowing, or noisy sipping were also considered vulgar, and so, truly refined diners ate their soup in complete silence.

BYOC; bring your own cutlery

Forget bringing your own bottle, in early medieval and Tudor banquets, even the noblest of guests were expected to arrive with their own cutlery!

In fact, only the top table of highest-ranking diners were provided with utensils, while everyone else made do with the knives or spoons, typically made of horn, pewter, or silver, they’d brought from home.

What’s more, while knives were commonplace, forks were viewed with deep suspicion, considered foreign and effeminate well into the Elizabethan era.

Know your place

Forget sitting next to your bestie, status was everything in the Georgian dining room, with hosts following rigid rules about who sat where. The host took the head of the table, with the principal guest to his right and the second-ranking guest to his left, followed by the rest in strict descending order.

Husbands and wives were deliberately separated, and alternating ladies and gentlemen created a rhythm of conversation, prevented social cliques, and enforced the visual symmetry so prized at the time.

This carefully choreographed seating plan remained the gold standard well into the Edwardian era.

No kids allowed

In royal and aristocratic households of the 18th and 19th centuries, dining as a family was practically unheard of. Queen Victoria famously rarely ate with her children, who were instead confined to the nursery and fed by nannies, and most upper-class children only saw their parents once or twice a day, typically during a formal morning visit or just before bed.

The idea of “dining en famille” for posh folk only started to gain traction during the reign of Edward VII, as changing social attitudes made family mealtimes more acceptable.

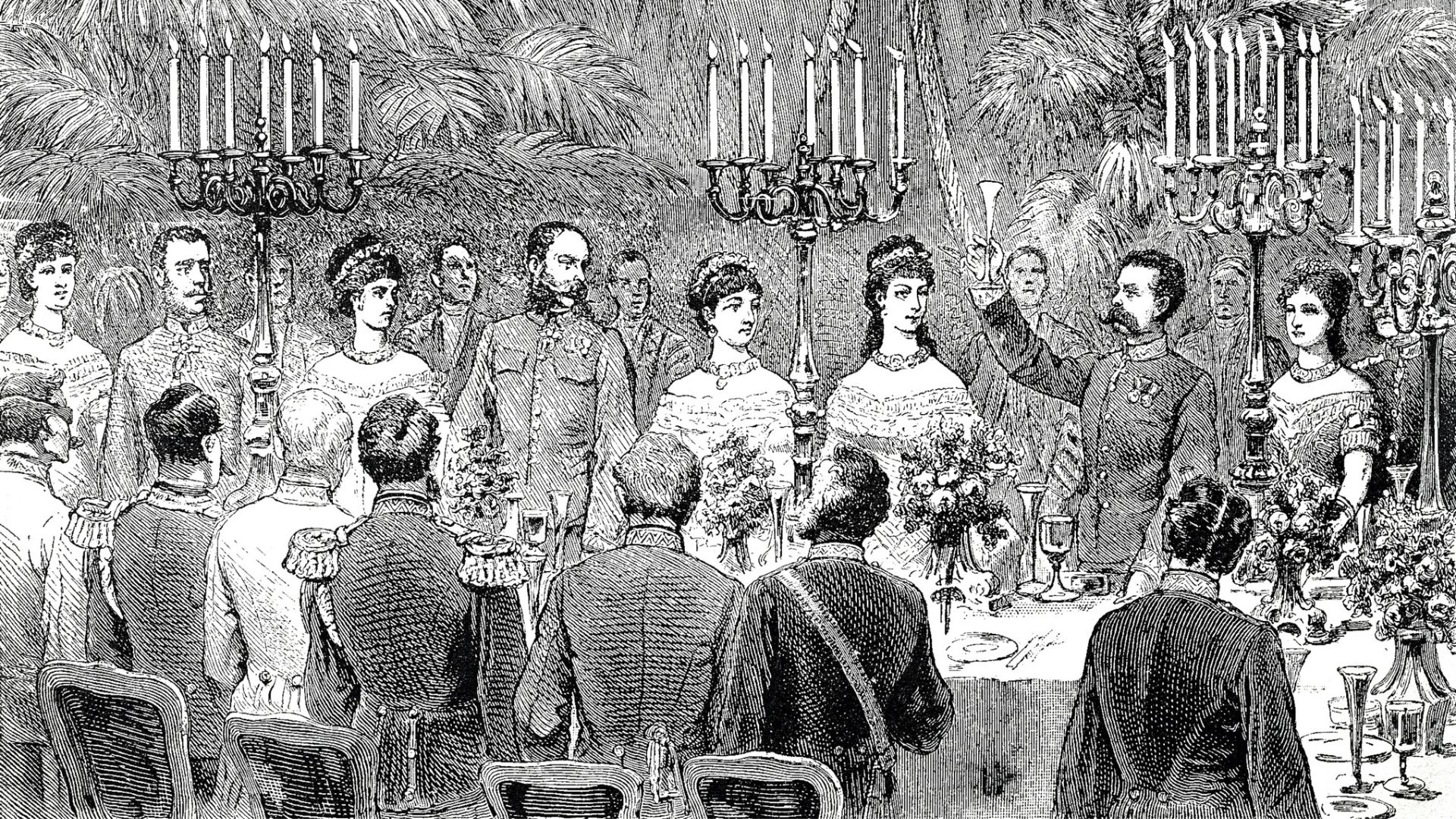

Fanfare and feast

At royal banquets from the medieval through Renaissance eras, food wasn’t simply eaten, it was performed! Dishes of great importance were paraded into the hall with trumpets, jesters, or heraldic banners, creating fanfare that reinforced the host’s power and prestige.

Between courses, guests were also treated to entremets; theatrical spectacles staged right at the table.

These could include roasted boar’s heads, bedecked with fruit and herbs, carried in to fanfare and applause, silver fountains bubbling with spiced wine or rosewater, or elaborate edible landscapes and pastry ships crafted purely for admiration.

It was less about taste and more about showing off in the most spectacular way.

Retiring gracefully

In high society from the 18th to early 20th century, dessert didn’t just mark the end of the meal, it signalled the start of a genteel disappearing act. The ladies would retire to the drawing room, while the gentlemen lingered over port, cigars, and political grumbling.

This post-pudding split reflected the era’s “separate spheres” thinking, but linger too long with your port and you risked offending the hostess; leave too soon and you might miss the scandal!

The prestige of pineapples

Forget fine wine and flashy cutting-edge tech, the aristocratic dining-room trophy of yesteryear was the pineapple.

Bursting onto the scene in Restoration England, with even Charles II famously painted receiving one, the pineapple was the thing to have at one’s dinner party during the Georgian era, with each one said to cost the modern equivalent of several tens of thousands, and as such was considered far too precious to eat.

Instead, it became a prized centrepiece, paraded at banquets and placed atop ornate platters. Renting pineapples or cultivating them in costly heated “pineries” soon became widespread among the upper classes keen on imitating the aristocracy.

Soon, no high-society dinner party was complete without one.

Crystal and silver for show

Those Georgians sure loved their bling, and the obsession with sparkle and splendour carried right through the Regency, Victorian, and Edwardian eras.

From monogrammed crystal finger glasses to embossed silver cutlery, engraved pudding trowels, and delicately curved oyster forks, aristocratic tableware was just as much about prestige as practicality.

And, in the grandest royal and noble households, even the salt had its own ceremony, with its own servant! The Yeoman of the Silver Pantry, who was in charge of silver service, was responsible for polishing and placing the salt cellars with ritual precision.

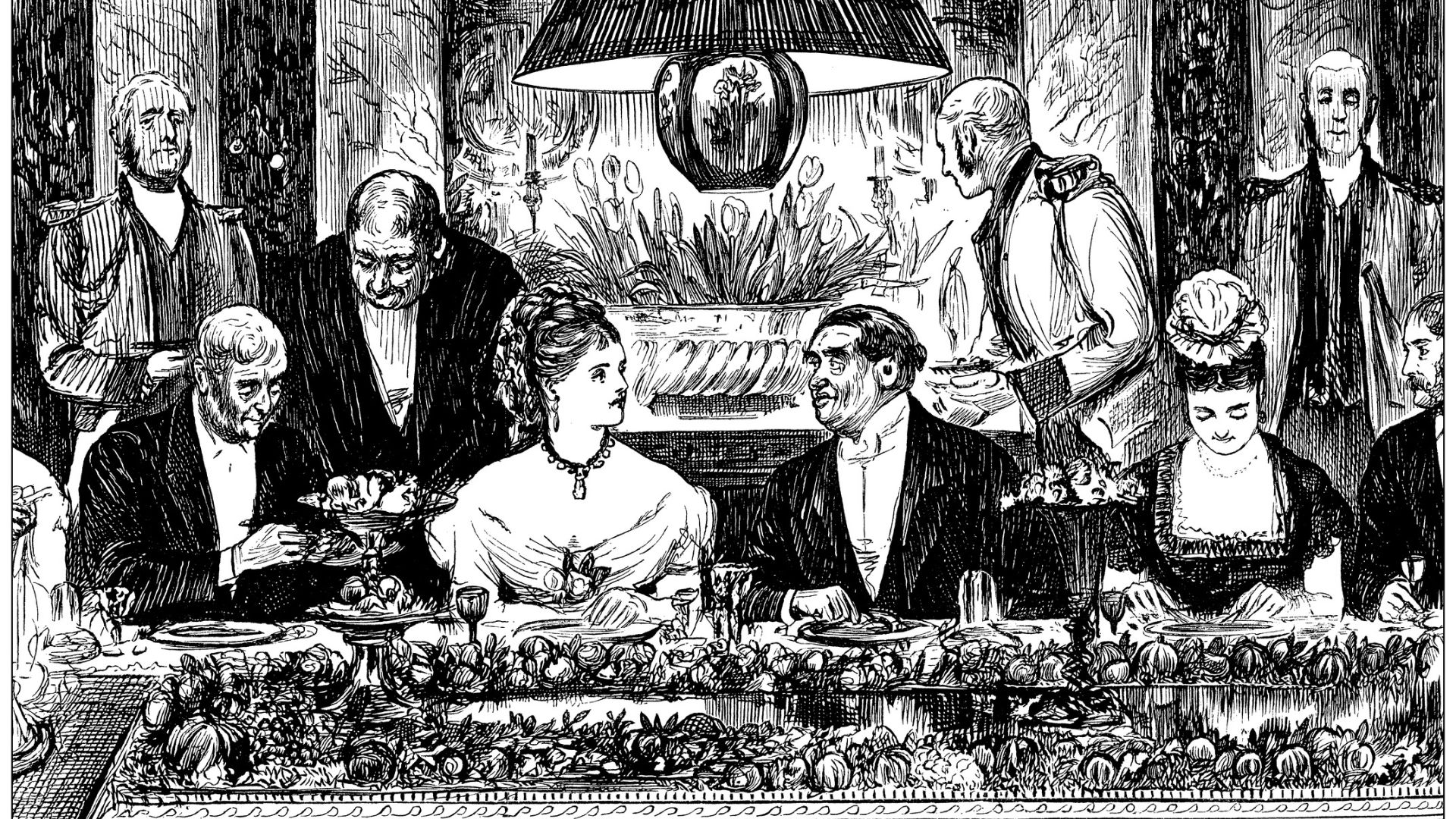

À la Française to À la Russe

Long before modern tasting menus, aristocratic feasts were about pure spectacle. From the Middle Ages to the early 1800s, meals were served à la française, with every dish of a course brought out at once in a dazzling, symmetrical display.

Tables groaned under the weight of roasted meats, game pies, sugared fruits, and elaborate centrepieces, sometimes up to 96 dishes at a time, because it wasn’t just about eating; it was about impressing! But in 1810, Russian ambassador Alexander Kurakin introduced service à la Russe to France, with courses served one by one.

Slower, sleeker, and more refined dining followed, spreading through high-society Europe to become the elegant standard we still recognise today.

Dinner dates by design

In grand aristocratic homes from the Georgian era through to late Victorian times, dinner didn’t begin with the food, it began with ceremony!

Before anyone so much as glanced at a soup spoon, the host would assign each gentleman a lady to escort into the dining room, always following a strict social pecking order, in what was essentially a carefully choreographed show of status.

While the tradition faded in the early 20th century as social formality began to soften, you can still spot echoes of the tradition in modern state banquets and debutante events today.

Salt: the ultimate social divider

Think salt is simply used for seasoning one's food? Think again! To sit “above the salt” was a clear and visible marker of privilege in medieval and Tudor dining halls. The host’s honoured guests were seated between the head of the table and the all-important salt cellar, while those of lesser rank were placed “below the salt” further down.

In those days, salt was a valuable commodity, and its placement quite literally divided the elite from the merely respectable.

Wine needs its own butler

In aristocratic homes from the medieval period through to the Georgian era, the flow of drink was as tightly controlled as the guest list. The buttery, for ale and beer, and the wine cellar, for claret, sherry, and other prized imports, were housed in separate rooms and overseen by trusted staff who held real authority within the household.

These early sommeliers guarded the keys, tracked every bottle, and served drinks with ceremonial precision.

To catch a killer... use a spoon

In Tudor times, being invited to dinner was sometimes less a social affair and more the inspiration for a literal backstabbing scene from Game of Thrones. So widespread was the fear of poisoning that some well-to-do lords and ladies, believing silver spoons could detect arsenic by darkening on contact, brought their own for protection.

Unfortunately, while silver can tarnish when exposed to sulfur compounds found in some poisons, it also reacts to harmless ingredients like eggs or wine, thus occasionally resulting in dramatic, if rather unfounded, accusations. Awk-ward!

Raise a glass (if rank allows)

While today anyone can raise a glass if the feeling takes them, at well-to-do Georgian and Regency dinners, toasting followed a strict hierarchy, with only the host or principal guests permitted to initiate the first toast, then working down the social pecking order. What’s more, timing was everything: jump in too early or toast the wrong person, and you risked serious offence.

Even the act of raising a glass came with specific rules: stand, raise, sip, and nod with decorum. It was part performance, part diplomacy, and a single misstep could cause a social stir no amount of fine wine could smooth over.

The language of luxury

In Victorian and Edwardian Britain, menus weren’t just about what tasted delicious, they were about what sounded delicious, more specifically, en français!

Even when dining in a grand English manor, aristocratic hosts printed their menus entirely in French, not because people understood them, but because French was universally accepted as the language of elegance, sophistication, and impeccable taste.

It hinted at a French-trained chef behind the scenes and a hostess with a fashionable, continental flair. The tradition lingered well into the early 20th century, only fading after the First World War, when English pride and simpler tastes began to reclaim the table.

Napkin signals and social codes

In 18th-century France, napkins weren’t just for dabbing the corners of one’s lips, they were part of a carefully choreographed dining ritual! Decorum dictated that the highest-ranking guest should unfold theirs first, with the rest of the table following suit.

There was also no blotting of brows, no tucking into collars, and folklore even claims that folding a napkin in certain ways revealed secret messages, like a point towards a monarch was seen as a silent threat.

Breakfast rules

In aristocratic households of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, breakfast was one of the only meals with a touch of flexibility. Gentlemen might help themselves to kippers, kidneys, or kedgeree from a buffet laid out for them in the Morning Room, while married ladies were often served breakfast in bed.

Meanwhile, unmarried daughters were still expected to dress and take breakfast downstairs with their fathers. The tradition only began to fade after World War I, as households reduced staff and rigid etiquette relaxed across all mealtimes.

When toasts need a master

From as far back as the late medieval period through to the Victorian era, heralds and toastmasters brought theatrical flair to aristocratic dining, announcing guests, introducing courses, and orchestrating royal toasts with booming voices and impeccable timing. But this tradition was temporarily paused during Oliver Cromwell’s Interregnum (1649–1660), when such pomp was viewed as sinful excess.

The ceremonial roles were resurrected again caraduring the Restoration, when the “Merry Monarch” Charles II gleefully revived full-blown pageantry.

Eat by example

Even now, royal dining remains a tightly choreographed affair. Guests at state banquets are met with 12-piece silverware settings from George IV’s Grand Service, dress codes that require tiaras and white tie, and menus pre-approved by the monarch, often minus garlic or shellfish, depending on their particular preferences.

One of the longest-standing rules of decorum is that once the monarch stops eating, so must everyone else. Not out of reverence, but to keep the meal running precisely to time.

Gauche to gush

In polite Victorian and Edwardian high society circles, if you didn’t like your meal, or worse, found something unpleasant in your food, be it a hair, bone, or even a bug, you were always expected to stay silent.

Instead, decorum dictated that you hand your plate to the nearest servant without a word, and carry on as if nothing had happened. Commenting on the food in any way, even to offer praise, was considered terribly gauche and not the done thing.

Class by cutlery count

In Victorian and Edwardian times, how you (or more specifically, your footman) laid the table wasn’t just about function, it was a test of class. From oyster forks to pudding spoons, the sheer variety of cutlery beside your plate reflected the meal’s complexity and, more subtly, your pedigree. This was a time when quantity and quality mattered in equal measure!

What’s more, ladies were expected to arrive gloved, only removing their gloves discreetly before touching one of the many, many utensils.

No applause necessary

In 18th and early 19th-century royal and aristocratic households, dinner entertainers were heard, but rarely acknowledged, as musicians were there to provide elegant ambience, not to take a bow. Clapping was considered unspeakably gauche, and so instead appreciation was shown through a discreet nod from the host.

It wasn’t until the Victorian era loosened some of these rigid rules that a little polite applause began to sneak in, but even then, only in the most carefully curated circles.

Scent and status

From Georgian through to Victorian times, tiny bunches of flowers, known as nosegays, were often placed at each setting during grand dinners and special balls.

More than being just pretty, these posies added a fragrant touch of refinement that subtly masked the odours of crowded halls and candlelit feasts. Tied with ribbon or tucked into napkins, they could also carry symbolic meaning, conveying favour or romance through the secret language of flowers.

Cross knives and be damned

At aristocratic tables, leaving your knives crossed on the plate wasn’t just bad manners, it was likely to invite a quarrel! The superstition is thought to stem from old folk beliefs that crossed blades disrupted harmony or carried negative energy, with distant echoes of the time when such symbols were associated with war, witchcraft and misfortune.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, however, the upper classes had transformed this into a matter of silent social etiquette, with well-bred guests taking care to place their knives in neat, parallel lines.

Ritual handwashing

At fancy medieval banquets, nobles washed their hands before and after meals with scented water poured by attendants from ornate ewers into basins. This was a practical measure, as fingers were used for eating instead of forks, but the act was just as much a display of hierarchy as it was about hygiene, with hands cleansed in strict order of rank.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, this ritual evolved into the refined custom of finger bowls, with guests offered delicate basins of warm water, subtly infused with rose petals, citrus peel, or orange blossom, between dessert and fruit courses to refresh their fancy fingertips.

Conversation by course

In Georgian, Regency, Victorian, and Edwardian high society, even small talk at dinner parties had a system, and it was of paramount importance to stick to it or be socially shunned!

Traditionally at formal occasions, it was the gentlemen who carried the conversational choreography, speaking first to the lady on their right during the opening course, then switching to the left for the next. The ladies, meanwhile, remained graciously in place, responding in turn. This subtle ritual ensured variety and balance around the table.

Coordinated to impress

From the Georgian through to the Edwardian era, the upper-crust households took their styling very seriously. Footmen and butlers were expected to wear liveries in colours and exact shades that matched the family’s crest and often, during special dinners, even coordinated with the table linens and porcelain.

The result was a perfectly orchestrated dining tableau that spoke volumes about the hosts’ wealth and taste, without them having to say a word.

The curse of 13

Across aristocratic Europe, particularly in Regency England, seating exactly 13 guests at the dinner table was seen as a serious faux pas. The superstition traces its roots to Christian and Norse folklore with Judas said to be the 13th guest at the Last Supper, while Loki crashed a banquet in Valhalla as the uninvited 13th, bringing chaos in his wake.

As such, high-society hosts would go to great lengths to avoid the unlucky number, often drafting in a last-minute guest to restore balance. The belief has endured in popular culture too. For instance, in Lord Edgware Dies (also published as Thirteen at Dinner), Agatha Christie sets up a dinner with exactly 13 guests, with one character commenting on the ill omen, warning that the first to leave the table may be cursed.

Invisible service

In grand houses from the Regency to the Edwardian era, dinner wasn’t just a meal, it was a performance, and the servants were well versed in their choreography. Footmen were trained never to face guests directly, gliding silently around the table with precision, backs turned to preserve the illusion of intimacy.

Every movement was rehearsed: where to stand, when to step, how to serve, with each butler and footman operating in designated “zones”. If the performance was done right, no one noticed them at all.

Natalie Denton is a freelance writer and editor with nearly 20 years of experience in both print and digital media. She’s written about everything from photography and travel, to health and lifestyle, with bylines in Psychologies, Women’s Health, and Cosmopolitan Hair & Beauty. She’s also contributed to countless best-selling bookazines, including Healthy Eating, The Complete Guide to Slow Living, and The Anti-Anxiety Handbook.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.