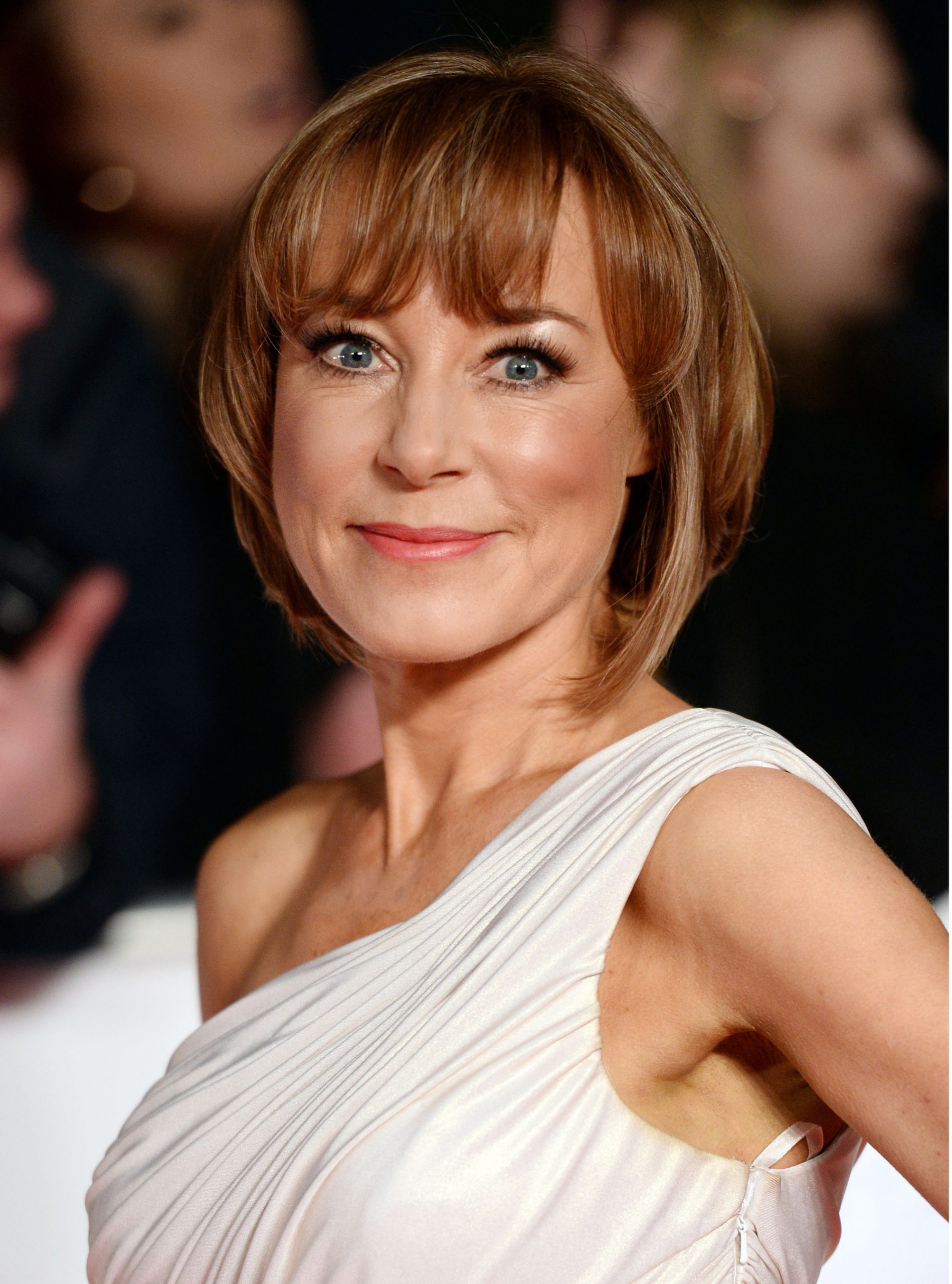

Sian Williams On Learning To Live With Fear And Uncertainty

Sian, 51, has two adult sons from her first marriage, a stepdaughter of 19, and a son and daughter aged ten and seven, from her marriage to journalist Paul Woolwich. The family live in Kent.

This Christmas will be chaotic. I know it is for most of us - the usual few days full of squabbling and tears, laughter and hugs. Paul preparing a massive lunch, spending hours by the oven, wine glass in hand, Radio 4 blaring. Meanwhile by the tree, the adult children feigning excitement when they get yet another jumper, the "babies" ripping the paper off their gifts, barely looking at the one they've just been given. So yes, the usual happy, messy, mad Christmas. With the added complication that we have all five children with us this year and only two single beds.

We're in a short-term holiday let, booked because our house needs fixing and the builders... well, you know how it is. So all seven of us are in a tiny cottage in a sleepy village with very little space. A potential pressure cooker of emotion. And yet - what a joy to have them all under one roof. The relief I feel when I look around the room and there they all are. Safe.

Because it's been an appalling year of terror and fear. Shocking events in Europe; a truck being driven through a crowd of people watching fireworks in Nice, killing more than 80, injuring over 300. Islamists storming a French country church and slitting the throat of the elderly priest. Horrific, inexplicable, ghastly acts of violence and ones when your brain can't help but start racing - is my family OK? Where are my children?

In fact the chances of being caught up in a terror attack are tiny. One study a few years ago suggested you're more likely to be killed by a bee sting.

And yet still we behave differently after an attack. We become more hyper-vigilant, always looking to see where the violence may come from. We feel we have no control because, in truth, we don't. An attack can come from anywhere, from anyone, in any form. How can we protect ourselves from that? How can we live with that fear?

That is the point of terrorism - to instil this panic, to pollute our sense of freedom.

Sign up to our free daily email for the latest royal and entertainment news, interesting opinion, expert advice on styling and beauty trends, and no-nonsense guides to the health and wellness questions you want answered.

So we become distrustful of others. We get twitchy if we sit next to someone on the tube carrying a backpack, jumping to conclusions if they're from a different culture, speaking an unknown language. The stories of the innocent becoming the suspect are legion. An Iraqi-born man, about to fly from Vienna to London, texted his wife to say he'd be late. It was in Arabic and a fellow passenger informed the flight crew, who asked him to leave the plane. The authorities held him for four hours. A mental health worker on another flight was detained after being seen reading a book on Syria. Thousands of Muslims are being stigmatised and alienated because of our lack of understanding, and that plays right into the hands of those who want to harm us.

"They" are so-called Islamic State, claiming every new atrocity even if the link is tenuous, keeping their well-oiled publicity machine going. Sometimes though, an attack has nothing to do with their perverted religion. Sitting at my news desk in the office, an alert pings up onto my computer screen. "Stabbing in London's Russell Square, one killed, several injured, no further details." Instantly, a team is sent to the scene, calls are made to find out what is happening and, amid all the public fact-finding, there's that private fluttering in the stomach, a silent hum of fear. Who do I know who works around there? Is everyone safe?

Those I know were, but relief is always tinged with guilt. Someone's been robbed of a loved one forever. The cause of the tragedy wasn't extremists this time - it was someone with a mental health problem. Should we start being anxious about that as well? One in four of us has mental health issues - are we really going to start looking around us to try to work out who may have a serious, pathological disorder that may make them murderous? Of course not.

And yet, we are primed to react like this. There's a tiny bit of our brain called the amygdala, which alerts us to fear and threat. When we're escaping from a predator, it clicks into gear, together with a rush of hormones. Quick! Fight! Flight! Freeze! It's unthinking, reactive and instinctive. It's activated when we are in a state of heightened stress so if we're frightened about a possible attack on our city day trip or worrying about the nervous guy sitting opposite us on the train, clutching a bag, it's working overtime. It's also suppressing the rational part of the mind that provides context, the bit that reminds us of the low odds of an atrocity or gives us an alternative reason for the anxious passenger.

We can't think straight when we are hyper-alert because we're programmed to escape and the calm, decision-making functions of our brain are temporarily switched off. Psychologists call it "catastrophisation", thinking the worst, but there is a way of stopping it.

Firstly, name the fear. The very act of saying it out loud or writing it down gives you a distance and engages a different part of the mind, to help manage your emotions. Then evaluate that fear. How likely is it to happen? Look at other explanations for your sudden burst of anxiety too. You won't always have answers and you may still feel vulnerable but if you can reflect on why you may be worried, you can take care of yourself through it.

It's about living with uncertainty. I had cancer last year and kept thinking about it returning, and I remember my very wise oncologist saying to me, "Sian, if you're always waiting for the worst to happen, then it may as well already have happened because it's changing the way you feel about life and the way you view yourself."

Be proactive with your fear. One colleague of mine says when she goes to an airport she thinks, "We could all be targeted here." So, she's come up with a routine. While she's checking her passport and tickets, she's looking for her nearest exit route too. "It sounds bonkers," she says, "but once I know how to escape, I start to relax." Her friend has given her nanny a checklist of "what to do in the event of an attack" - where to take the kids, the phone number of the nearest hospital.

Whatever logic you use to help you feel more comfortable with anxiety, take it, use it and then move on with living.

My cancer diagnosis came just before Christmas a couple of years ago - the double mastectomy was planned for the week afterwards and yet it wasn't a miserable time. It focused all our minds on what, or rather who, mattered and I cherished every chaotic moment. So this year, whatever the uncertainty, try to let your thoughts be the gratitude and joy you feel being with friends and family, not the fear you feel about losing them.

And if for you, Christmas is a quiet, reflective time when your mind turns to those who aren't with us, maybe these words from a traditional Indian prayer will help you, as they did me, after the loss of my mum. "Think of me now and again, as I was in life... and while you live, let your thoughts be with the living."

Sian Williams is ITN's first mental health ambassador and a trained trauma assessor with an MSc in Psychology. Her bookRise: Surviving and Thriving after Trauma

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson) is out in paperback on 29 December.